Please Help Us Keep These Thousands of Blog Posts Growing and Free for All

$5.00

|

|

|

Most Christian millennialist thinking is based upon the Book of Revelation, specifically Revelation 20, which describes the vision of an angel who descended from heaven with a large chain and a key to a bottomless pit and captured Satan, imprisoning him for a thousand years:

2 And he seized the dragon, the original serpent, who is the Devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years; 3 and threw him into the abyss,[41] and shut it and sealed it over him, so that he might not deceive the nations any longer, until the thousand years were ended; after these things he must be released for a short time.

— Revelation 20:2-3 (UASV)

The Book of Revelation then describes a series of judges who are seated on thrones, as well as John’s vision of the souls of those who were beheaded for their testimony in favor of Jesus and their rejection of the mark of the beast. These souls:

4 Then I saw thrones, and they sat on them, and judgment was given to them. And I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded[42] because of their testimony of Jesus and because of the word of God, and those who had not worshiped the beast or his image and had not received the mark on their forehead and on their hand; and they came to life and reigned with Christ for a thousand years. 5 (The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were completed.) This is the first resurrection.[43] 6 Blessed and holy is the one who has a part in the first resurrection; over these the second death has no power, but they will be priests of God and of Christ and will reign with him for a thousand years.

— Revelation 20:4-6 (UASV)

|

|

|

Early Church

During the first centuries after Christ, various forms of chiliasm (millennialism) were to be found in the Church, both East and West. It was a decidedly majority view at that time, as admitted by Eusebius, himself an opponent of the doctrine:

The same writer (that is to say, Papias of Hierapolis) gives also other accounts which he says came to him through unwritten tradition, certain strange parables and teachings of the Saviour, and some other more mythical things. To these belong his statement that there will be a period of some thousand years after the resurrection of the dead, and that the kingdom of Christ will be set up in material form on this very earth. I suppose he got these ideas through a misunderstanding of the apostolic accounts, not perceiving that the things said by them were spoken mystically in figures. For he appears to have been of very limited understanding, as one can see from his discourses. But it was due to him that so many of the Church Fathers after him adopted a like opinion, urging in their own support the antiquity of the man; as for instance Irenaeus and any one else that may have proclaimed similar views.

— Eusebius, The History of the Church, Book 3:39:11-13

|

|

|

Nevertheless, strong opposition later developed from some quarters, most notably from Augustine of Hippo. The Church never took a formal position on the issue at any of the ecumenical councils, and thus both pro and con positions remained consistent with orthodoxy. The addition to the Nicene Creed was intended to refute the perceived Sabellianism of Marcellus of Ancyra and others, a doctrine which includes an end to Christ’s reign and which is explicitly singled out for condemnation by the council [Canon #1]. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that the 2nd century proponents of various Gnostic beliefs (themselves considered heresies) also rejected millenarianism.

Millennialism was taught by various earlier writers such as Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Commodian, Lactantius, Methodius, and Apollinaris of Laodicea in a form now called premillennialism. According to religious scholar Rev. Dr. Francis Nigel Lee, “Justin’s ‘Occasional Chiliasm’ sui generis which was strongly anti-pretribulationistic was followed possibly by Pothinus in A.D. 175 and more probably (around 185) by Irenaeus”. Justin Martyr, discussing his own premillennial beliefs in his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, Chapter 110, observed that they were not necessary to Christians:

I admitted to you formerly, that I and many others are of this opinion, and [believe] that such will take place, as you assuredly are aware; but, on the other hand, I signified to you that many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.

|

|

|

Melito of Sardis is frequently listed as a second-century proponent of premillennialism. The support usually given for the supposition is that “Jerome [Comm. on Ezek. 36] and Gennadius [De Dogm. Eccl., Ch. 52] both affirm that he was a decided millenarian.”

In the early third century, Hippolytus of Rome wrote:

And 6,000 years must needs be accomplished, in order that the Sabbath may come, the rest, the holy day “on which God rested from all His works.” For the Sabbath is the type and emblem of the future kingdom of the saints, when they “shall reign with Christ,” when He comes from heaven, as John says in his Apocalypse: for “a day with the Lord is as a thousand years.” Since, then, in six days God made all things, it follows that 6, 000 years must be fulfilled. (Hippolytus. On the HexaËmeron, Or Six Days’ Work. From Fragments from Commentaries on Various Books of Scripture).

Around 220, there were some similar influences on Tertullian, although only with very important and extremely optimistic (if not perhaps even postmillennial) modifications and implications. On the other hand, “Christian Chiliastic” ideas were indeed advocated in 240 by Commodian; in 250 by the Egyptian Bishop Nepos in his Refutation of Allegorists; in 260 by the almost unknown Coracion; and in 310 by Lactantius. Into the late fourth century, Bishop Ambrose of Milan had millennial leanings (Ambrose of Milan. Book II. On the Belief in the Resurrection, verse 108). Lactantius is the last great literary defender of chiliasm in the early Christian church. Jerome and Augustine vigorously opposed chiliasm by teaching the symbolic interpretation of the Revelation of St. John, especially chapter 20.

Around 220, there were some similar influences on Tertullian, although only with very important and extremely optimistic (if not perhaps even postmillennial) modifications and implications. On the other hand, “Christian Chiliastic” ideas were indeed advocated in 240 by Commodian; in 250 by the Egyptian Bishop Nepos in his Refutation of Allegorists; in 260 by the almost unknown Coracion; and in 310 by Lactantius. Into the late fourth century, Bishop Ambrose of Milan had millennial leanings (Ambrose of Milan. Book II. On the Belief in the Resurrection, verse 108). Lactantius is the last great literary defender of chiliasm in the early Christian church. Jerome and Augustine vigorously opposed chiliasm by teaching the symbolic interpretation of the Revelation of St. John, especially chapter 20.

In a letter to Queen Gerberga of France around 950, Adso of Montier-en-Der established the idea of a “last World Emperor” who would conquer non-Christians before the arrival of the Antichrist.

|

|

|

Reformation and Beyond

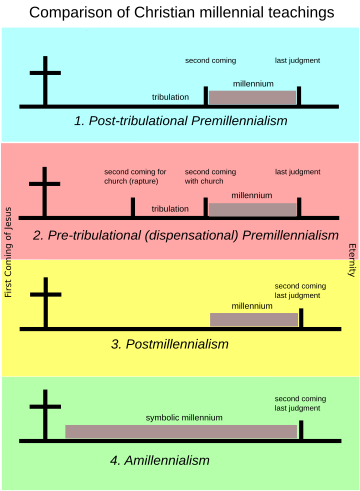

Comparison of Christian Millennial Interpretations

Comparison of Christian Millennial Interpretations

Christian views on the future order of events diversified after the Protestant reformation (c.1517). In particular, new emphasis was placed on the passages in the Book of Revelation which seemed to say that as Christ would return to judge the living and the dead, Satan would be locked away for 1000 years but then released on the world to instigate a final battle against God and his Saints. Previous Catholic and Orthodox theologians had no clear or consensus view on what this actually meant (only the concept of the end of the world coming unexpectedly, “like a thief in a night”, and the concept of “the antichrist” were almost universally held). Millennialist theories try to explain what this “1000 years of Satan bound in chains” would be like.

Various types of millennialism exist with regard to Christian eschatology, especially within Protestantism, such as Premillennialism, Postmillennialism, and Amillennialism. The first two refer to different views of the relationship between the “millennial Kingdom” and Christ’s second coming.

|

|

|

Premillennialism sees Christ’s second advent as preceding the millennium, thereby separating the second coming from the final judgment. In this view, “Christ’s reign” will be physically on the earth.

Postmillennialism sees Christ’s second coming as subsequent to the millennium and concurrent with the final judgment. In this view, “Christ’s reign” (during the millennium) will be spiritual in and through the church.

Amillennialism sees the 1000-year kingdom as being metaphorically described in Rev. 20:1–6, in which “Christ’s reign” is current in and through the church. Thus, while this view does not hold to a future millennial reign, it does hold that the New Heavens and New Earth will appear upon the return of Christ.

|

|

|

The Catholic Church strongly condemns millennialism as the following shows:

The Antichrist’s deception already begins to take shape in the world every time the claim is made to realize within history that messianic hope which can only be realized beyond history through the eschatological judgment. The Church has rejected even modified forms of this falsification of the kingdom to come under the name of millenarianism, especially the “intrinsically perverse” political form of a secular messianism.

— Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1995

19th and 20th Centuries

Bible Student movement

The Bible Student movement is a millennialist movement based on views expressed in “The Divine Plan of the Ages,” in 1886, in Volume One of the Studies in the Scriptures series, by Pastor Charles Taze Russell. (This series is still being published, since 1927, by the Dawn Bible Students Association.) Bible Students believe that there will be a universal opportunity for every person, past and present, not previously recipients of a heavenly calling, to gain everlasting life on Earth during the Millennium.

|

|

|

Is the Thousand Years Symbolic or Literal

Robert L. Thomas writes,

20:2 Swinging into action immediately, the angel seized and bound the dragon: καὶ ἐκράτησεν τὸν δράκοντα, ὁ ὄφις* ὁ ἀρχαῖος, ὅς ἐστιν Διάβολος καὶ ὁ Σατανᾶς, καὶ ἔδησεν αὐτὸν χίλια ἔτη (kai ekratēsen ton drakonta, ho ophis ho archaios, hos estin Diabolos kai ho Satanas, kai edēsen auton chilia etē, “and he seized the dragon, the serpent of old, who is the devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years”). The name τὸν δράκοντα (ton drakonta, “the dragon”), the first of Satan’s titles used here, is his most frequent title in Revelation (cf. 12:3, 4, 7, 13, 16, 17; 13:2, 4, 11; 16:13). Then follow the other names ascribed to him in 12:9.

The title ὁ ὄφις ὁ ἀρχαῖος (ho ophis ho archaios, “the serpent of old”) receives emphasis by being in the nominative case, though in apposition with the accusative ton drakonta (Lee). This type of phenomenon is frequent in Revelation, and is sometimes called an anacoluthon (e.g., 1:5) and sometimes a parenthesis. Διάβολος (Diabolos, “The devil”) is the name that refers to this divine opponent in 2:10; 12:9, 12; 20:10. Ὁ Σατανᾶς (Ho Satanas) refers to him in 2:9, 13, 24; 3:9; 12:9.

|

|

|

The binding of a spiritual being such as ἔδησεν (edēsen, “bound”) depicts is a mystery to humans accustomed to the material world only. Whatever it is, it is the same as the binding of the angels in 9:14 which prohibited their movement and activity (Swete). The idea behind this securing of the great enemy is probably the same as that in Isa. 24:22–23 (Charles).

The duration of the binding is χίλια ἔτη (chilia etē, “a thousand years”), an accusative expressing extent of time. The sixfold repetition of this number of years (cf. 20:3, 4, 5, 6, 7) indicates its great importance (Lee). Exegetes have expressed different understandings of this period whose duration of one thousand years was undisclosed until John wrote this (Charles). One school of thought voices concern over even discussing the issue for fear of creating strife among the saints. This view emphasizes that God’s clock does not follow our reckoning, so humans cannot know what “a thousand years” means. This view looks to 2 Pet. 3:8 for support, but 2 Pet. 3:8 along with Ps. 90:4 states the very opposite. “A thousand years” in these two verses refers to a literal thousand years. To say that the period with man is only one day with God, does not deny that it is actually a thousand years with God too (Walvoord). The point is that time does not limit an eternal God, not that He is ignorant of what time means with man. Another feature opposed to this agnostic approach to the meaning of “a thousand years” is that this writer, when he wants to speak of an indefinite time, uses something like μικρὸν χρόνον (mikron chronon, “a little time”) (20:3) rather than give an explicitly definite period of time.

|

|

|

Another way of handling the thousand-year period has been to view it as symbolic of a relatively long age of indefinite length. This explanation looks to the pattern of using numbers symbolically throughout Revelation for support. Most equate it with the period between Christ’s two advents, with the binding of  Satan being equal to the enlightenment of the nations through the gospel.22 As the largest conceivable unit of time in the Bible, it represents a period absolutely long just as “half an hour” (8:1) denotes a space of time absolutely short. All of this reasoning is exegetically futile, however, because it rests on preconceived theological dogma. The only semblance of exegetical support is the effort to equate the casting of the dragon from heaven in 12:7–9 with his casting into the abyss (20:3). But this equation is very doubtful, as already shown.

Satan being equal to the enlightenment of the nations through the gospel.22 As the largest conceivable unit of time in the Bible, it represents a period absolutely long just as “half an hour” (8:1) denotes a space of time absolutely short. All of this reasoning is exegetically futile, however, because it rests on preconceived theological dogma. The only semblance of exegetical support is the effort to equate the casting of the dragon from heaven in 12:7–9 with his casting into the abyss (20:3). But this equation is very doubtful, as already shown.

If the writer wanted a very large symbolic number, why did he not use 144,000 (7:1 ff.; 14:1 ff.), 200,000,000 (9:16), “ten thousand times ten thousand, and thousands of thousands” (5:11), or an incalculably large number (7:9)? The fact is that no number in Revelation is verifiably a symbolic number. On the other hand, nonsymbolic usage of numbers is the rule. It requires multiplication of a literal 12,000 by a literal twelve to come up with 144,000 in 7:4–8. The churches, seals, trumpets, and bowls are all literally seven in number. The three unclean spirits of 16:13 are actually three in number. The three angels connected with the three last woes (8:13) add up to a total of three. The seven last plagues amount to exactly seven. The equivalency of 1,260 days and three and a half years necessitate a nonsymbolic understanding of both numbers. The twelve apostles and the twelve tribes of Israel are literally twelve (21:12–14). The seven churches are in seven literal cities. Yet confirmation of a single number in Revelation as symbolic is impossible.

|

|

|

So ample good reasons exist for not taking the number symbolically, but there are many good reasons for taking one thousand to be literal (Walvoord). It is the plain statement of the text six times. It is doubtful that any symbolic number, if there be such, is ever repeated that many times. Other symbolism in Revelation is not opposed to a literal understanding of the thousand years. The mention of the thousand years is not limited to the binding of Satan. John received the information by direct revelation apart from symbols also (cf. 20:4, 5, 6) (Walvoord). Alleged problems in identifying this kingdom with the one promised in the OT—such as its limited length, rather than being eternal, and its lack of the ideal conditions cited in the OT—are only apparent. The kingdom will have a limited phase and will enter its eternal phase after the conclusion of the thousand years. And it will have the ideal conditions described in the OT, but John has no occasion to mention them here.

The conclusion is that the only exegetically sound answer to the issue is to understand the thousand years literally.[1]

|

|

|

In Church History

Patristic Period. Those who regard millennialism as an alien import into the Christian faith have been much embarrassed by its early and widespread acceptance in the patristic Church. Salmond, for example, who considered millennial conceptions totally foreign to Christ’s teachings, had to admit that “the dogma of a Millennium … took possession of Christian thought at so early a date and with so strong a grasp that it has sometimes been reckoned an integral part of the primitive Christian faith” (p. 312).

Papias, who had personal contact with those taught by Christ and His apostles and may well have been a disciple of the apostle John, asserted that “the Lord used to teach concerning those [end] times” that “there will be a period of a thousand years after the resurrection of the dead and the kingdom of Christ will be set up in material form on this very earth” (cited in Eusebius HE iii.39.12; Irenaeus Adv. haer v.33.3f.). Though Papias fleshed out his millennial reference with details from 2 Baruch (see above), his account is a weighty testimony to primitive Christian eschatological beliefs.

|

|

|

The author of the Epistle of Barnabas (no later than a.d. 138) “is a follower of chiliasm. The six days of creation mean a period of six thousand years because a thousand years are like one day in the eyes of God. In six days, that is in six thousand years, everything will be completed, after which the present evil time will be destroyed and the Son of God will come again and judge the godless and change the sun and the moon and the stars and he will truly rest on the seventh day. Then will dawn the sabbath of the millennial kingdom (15, 1–9)” (Quasten, I, 89).

Justin Martyr, “the most important of the Greek apologists of the second century” (Quasten, I, 196), while granting that “many who belong to the pure and pious faith and are true Christians think otherwise” than he on the millennial issue, explicitly declared: “I and others are right-minded Christians in all points and are assured that there will be a resurrection of the dead and a thousand years in Jerusalem, which will then be built, adorned and enlarged” (Dial. 80f.; cf. J. Daniélou, VC, 2 [1948], 1–16).

Other important patristic millennialists were Irenaeus (see below, the final quotation in this article); Hippolytus of Rome and Julius “Africanus” (see Froom, I, 268–282, and note his helpful tabular summary of patristic views, pp. 458f); Victorinus of Pettau, the chiliasm of whose commentary on Revelation was edited out by amillennialist Jerome (see Quasten, II, 411–13; Froom, I, 337–344); and the Africans Tertullian (AdvMarc iii.24; Apol 48; cf. Quasten, II, 318, 339f), Cyprian (see Froom, I, 331–36), and Lactantius (whose detailed picture of millennial bliss in Divine Institutes vii.14, 24, 26 by no means presupposes Zoroastrian influence—Eliade notwithstanding). In taking a millennial viewpoint, these fathers ranged themselves on the side of orthodoxy in two particulars: they supported the apostolicity and canonicity of Revelation (against those who combined a denial of its authenticity with amillennialism, e.g., Dionysius of Alexandria, as cited in Eusebius HE vii.14.1–3; 24.6–8); and they opposed both the Gnostics, whose dualistic spiritualizing of Christian doctrine completely wiped out eschatological hope, and Christian Platonists such as Origen (De prin. ii.11.2), whose rejection of a literal millennium stemmed from an idealistic depreciation of matter and a highly dangerous allegorical hermeneutic (A. C. McGiffert, History of Christian Thought, I [1932], 227f).

|

|

|

It is a moot point whether the Clementine epistles, the Shepherd of Hermas, the Didache, the Apocalypse of Peter, Melito of Sardis, the letters of the Lyons martyrs, Methodius of Tyre, and Commodian show traces of millennialism. Polycarp of Smyrna and Ignatius of Antioch certainly do not—but little can be derived one way or the other from arguments from silence. Active opposition to chiliastic views arose (1) as a result of Origen’s influence (thus Eusebius’s later shift to amillennialism, HE iii.39, with his false attribution of chiliastic origins to the heretic Cerinthus, HE iii.28); (2) in reaction to Montanist excesses, e.g., their prophetess’s claim that “Christ came to me in the form of a woman … and revealed to me that this place [the insignificant village of Pepuza] is holy and that here Jerusalem will come down from heaven” (Epiphanius xlix.1; cf. McGiffert, I, 171); and (3) as a defense against attempts to calculate the end time (a practice that has consistently brought discredit, through guilt-by-association, to millennialism in every age: e.g., cf. Vulliaud, pp. 75–85; Toulmin and Goodfield, Discovery of Time [1965], pp. 55–73; M. J. Forman, Story of Prophecy [1940]; R. Lewinsohn, Science, Prophecy and Prediction [1961]; L. Festinger, etal, When Prophecy Fails [1956]; T. C. Graebner, Prophecy and the War [1918]; War in the Light of Prophecy [1941]; and finally, as an especially gross modern example, O. J. Smith, Is the Antichrist at Hand? What of Mussolini [1927]).

Middle Ages and Reformation. No theologian of the ancient Church had a greater influence on its history during the medieval period than Augustine. Once a chiliast himself but driven away from that position by the “immoderate, carnal” extremism of some of its advocates (Civ. Dei xx.7), he followed the symbolical-mystical hermeneutic system of the fourth-century donatist Tyconius in arguing that the thousand years of Rev. 20 actually designated the interval “from the first coming of Christ to the end of the world, when He shall come the second time” (xx.8). Thus was “a new era in prophetic interpretation” introduced, wherein Augustine’s conception of the millennium as “spiritualized into a present politico-religious fact, fastens itself upon the church for about thirteen long centuries” (Froom, I, 479, with tabular summary of medieval views, 896f; see also R. C. Petry, Christian Eschatology and Social Thought: A Historical Essay on the Social Implications of Some Selected Aspects in Christian Eschatology to a.d. 1500 [1956], pp. 312–336). Millennialism did not die, but under the pressure of the “medieval synthesis” it tended to assume aberrational forms, particularly after the year 1000 when the Augustinian chronology (if literalized) ran out. Thus, as is frequently the case, polar extremes developed: mystical, spiritualistic chiliasms presupposing the end of the church-age, as represented by Joachim of Fiore’s “third age of the Spirit,” and by Cathari, Spiritual Franciscans, and Waldenses; and grossly materialistic chiliasms bound up with the crusading enterprise, as illustrated by Urban II’s speech at Clermont: “As the times of Antichrist are approaching and as the East, and especially Jerusalem, will be the central point of attack, there must be Christians there to resist.” (On both varieties of medieval chiliasm, see J. J. von Döllinger The Prophetic Spirit and the Prophecies of the Christian Era, published with his Fables Respecting the Popes [1872]; A. Vasilev, Byzantion [1942/43], pp. 462–502; R. A. Knox, Enthusiasm [1950], pp. 110–13; and esp. N. Cohn, Pursuit of the Millenium … in Europe from the 11th to the 16th Century [1961].)

Middle Ages and Reformation. No theologian of the ancient Church had a greater influence on its history during the medieval period than Augustine. Once a chiliast himself but driven away from that position by the “immoderate, carnal” extremism of some of its advocates (Civ. Dei xx.7), he followed the symbolical-mystical hermeneutic system of the fourth-century donatist Tyconius in arguing that the thousand years of Rev. 20 actually designated the interval “from the first coming of Christ to the end of the world, when He shall come the second time” (xx.8). Thus was “a new era in prophetic interpretation” introduced, wherein Augustine’s conception of the millennium as “spiritualized into a present politico-religious fact, fastens itself upon the church for about thirteen long centuries” (Froom, I, 479, with tabular summary of medieval views, 896f; see also R. C. Petry, Christian Eschatology and Social Thought: A Historical Essay on the Social Implications of Some Selected Aspects in Christian Eschatology to a.d. 1500 [1956], pp. 312–336). Millennialism did not die, but under the pressure of the “medieval synthesis” it tended to assume aberrational forms, particularly after the year 1000 when the Augustinian chronology (if literalized) ran out. Thus, as is frequently the case, polar extremes developed: mystical, spiritualistic chiliasms presupposing the end of the church-age, as represented by Joachim of Fiore’s “third age of the Spirit,” and by Cathari, Spiritual Franciscans, and Waldenses; and grossly materialistic chiliasms bound up with the crusading enterprise, as illustrated by Urban II’s speech at Clermont: “As the times of Antichrist are approaching and as the East, and especially Jerusalem, will be the central point of attack, there must be Christians there to resist.” (On both varieties of medieval chiliasm, see J. J. von Döllinger The Prophetic Spirit and the Prophecies of the Christian Era, published with his Fables Respecting the Popes [1872]; A. Vasilev, Byzantion [1942/43], pp. 462–502; R. A. Knox, Enthusiasm [1950], pp. 110–13; and esp. N. Cohn, Pursuit of the Millenium … in Europe from the 11th to the 16th Century [1961].)

|

|

|

Both Renaissance and Reformation stood against the world view of medieval scholasticism, but they did not oppose the accepted Augustinian amillennialism. The Renaissance was too favorable toward Neoplatonic modes of thought to be chiliastic, and the Reformers were so (legitimately) preoccupied with correcting the Church’s soteriological errors that they could not give high priority to eschatology. But from the pre-Reformers Wyclif and Hus to Luther, Calvin, and the doctrinal affirmations of Protestant Orthodoxy, the papacy was identified with the antichrist. This conviction led many Reformation Protestants to believe that the end of the world was at hand (T. F. Torrance, SJT, Occasional Papers 2, pp. 36–62; Vulliaud, pp. 127f). Had it not been for the outbreak of chiliasm in a particularly offensive form at Münster (1534), early Church teaching on the millennium might have been recovered along with other doctrines obscured in the medieval synthesis. The speculations of radicals, however, as concretized in Münzer’s “Zion,” were so offensive to all that this was rendered impossible. The Augsburg Confession, art 17 (Lutheran) and the Helvetic Confession, art 11 (Reformed) expressly rejected such “Jewish opinions” (but, let it be noted, did not reject millennialism per se—cf. Peters, Theocratic Kingdom, I, 531–34; M. Reu, Lutheran Dogmatics [1951], pp. 483–87; and Saarnivaara, pp. 94f).

|

|

|

Virtually all the Reformation commentators on Rev. 20 followed the Augustinian line, even when other aspects of their eschatology seemed to cry out for a millennial interpretation of the passage (cf. tabulation of views in Froom, II [1948], 530f). The same was true even of Anabaptists: “except for Melchior Hofmann, only a few fringe figures of the Anabaptist movement were chiliastic” (Mennonite Encyclopedia, I, 557). The oft-heard claim that theosophical mystic Jacob Boehme was a millennialist is repudiated by his own writings (cf. J. J. Stoudt, Sunrise to Eternity [1957], pp. 127f). In contrast, many of the seventeenth-century divines of the Westminster Assembly, e.g., Thomas Goodwin, were decidedly premillennial in their theology (cf. P. Schaff, Creeds of Christendom, I, 727–746); and “Cambridge Platonist” Henry More believed in a chiliastic future when “all the goodly Inventions of nice Theologers shall cease … and the Gospel shall be exalted” (see A. Lichtenstein, Henry More [1962], pp. 101f).

|

|

|

Modern Times. New England Puritanism, continental Pietism, and the evangelical revivals of the 18th cent. came long enough after the events of the Reformation that perspective on the Reformers’ limitations became possible. Among the results were increased missionary outreach and more careful eschatological study. Chiliasm revived, and it was generally of the premillennial variety (cf. the tabular summary of seventeenth-and eighteenth-century interpretations of Rev. 20 in Froom, II, 786f). Except for Jonathan Edwards, who was postmillennial (J. P. Martin, The Last Judgment … from Orthodoxy to Ritschl [1963], pp. 71f), virtually all the Christian leaders of colonial America maintained premillennialism: John Davenport; Samuel, Increase, and Cotton Mather; Samuel Sewall; Timothy Dwight (tabulation of views in  Froom, III, 252f; see also G. H. Williams, Wilderness and Paradise in Christian Thought [1962]). Spener, Halle Pietist and hymnwriter Joachim Lange, and distinguished NT scholar J. A. Bengel held millennial views. John Wesley’s hymns attest his early premillennarian belief, though later he embraced Bengel’s concept of a future double millennium (first on earth, with Satan bound; second in heaven, representing the saints’ rule with Christ).

Froom, III, 252f; see also G. H. Williams, Wilderness and Paradise in Christian Thought [1962]). Spener, Halle Pietist and hymnwriter Joachim Lange, and distinguished NT scholar J. A. Bengel held millennial views. John Wesley’s hymns attest his early premillennarian belief, though later he embraced Bengel’s concept of a future double millennium (first on earth, with Satan bound; second in heaven, representing the saints’ rule with Christ).

In sum, it can hardly be maintained, as is commonly alleged, that chiliastic belief did not have serious influence in Christendom before the rise of Adventist sects and J. N. Darby’s Plymouth Brethren in the 19th cent., and the appearance of the Scofield Reference Bible and the Fundamentalist movement early in the 20th cent. (cf. W. H. Rutges, Premillennialism in America [1930]; L. Gaspar, The Fundamentalist Movement [1963], pp. 7f, 53f, 157). Certainly Darby and the Scofield editors introduced the Church to dispensationalism (at least as a formal theology), and premillennialism was an essential element in that hermeneutical schema; but a premillennarian view of Rev. 20 did not logically require dispensational commitment and had in fact existed independently of it since the early days of the Church.

|

|

|

Utopian Dream. Secular utopianism is a theme in the history of ideas correlative with the millennial hope, and it is instructive to note that where Christian millennial expectation has been absent or downplayed its utopian counterpart has entered the breach. Greco-Roman civilization conceived of history cyclically, with the “golden age” as a future hope (cf. Vergil’s 4th Eclogue). During the amillennial Middle Ages the legend of an idealistic kingdom in the East, under the rule of Christian “Prester John,” captured the imagination and directly influenced the mythology of exploration (Ponce de Leon’s search for the fountain of youth, Pizarro’s quest for a city of gold). The Renaissance, similarly unsympathetic to chiliasm, marked the beginning of literary utopianism with the work of Thomas More. The rise of the modern secular era during the deistic “Enlightenment” offered a secular alternative to the Christian millennium in what Carl Becker perceptively termed “the heavenly city of the 18th-century philosophers.” The Marxist goal of a “classless society,” the Nazi dream of the “thousand-year Reich,” and aspects of the capitalist-materialist “American way of life” are inversions of the millennial hope. E. Voegelin (Order and History [1956]) has rightly seen them as illustrations of “metastatic gnosis,” the idolatrous effort of man to create a millennial kingdom for himself without God. It would appear that the loss of theocentric chiliasm leaves a vacuum into which rush the monstrosities of anthropocentric utopianism. At the same time, perennial utopian dreams (and extrabiblical religious chiliasms, as in the Parsi faith—see I.C above) can be viewed as the groping of the human soul, individual and collective, for the truth embodied in Christian eschatology. (See, e.g., S. Baring-Gould, Curious Myths of the Middle Ages [1866–1868]; K. Mannheim, Ideology and Utopia [1936]; E. Sanceau, The Land of Prester John [1944]; F. R. White, ed., Famous Utopias of the Renaissance [1946]; K. Amis, New Maps of Hell [1960]; S. B. Liljegren, Studies on the Origin and Early Tradition of English Utopian Fiction [1961]; J. P. Roux, Les Explorateurs au moyen âge [1961]; R. Thévenin, Les Pays légendaires [1961]; C. Walsh, From Utopia to Nightmare [1962]; C. Kateb, Utopia and Its Enemies [1963]; Daedalus, Spring, 1965; L. Gallagher, More’s “Utopia” and Its Critics [1964]; E. L. Tuveson, Millennium and Utopia [1964]; H. B. Franklin, Future Perfect [1966]; M. R. Hillegas, The Future as Nightmare [1967]; T. Molnar, Utopia, the Perennial Heresy [1972]; J. W. Montgomery, Where Is History Going? [1969].)

|

|

|

Contrasting Millennialisms

Amillennial Allegory. Since chiliasm is bound directly to the interpretation of Rev. 20, consideration must be given to the diverse ways in which this passage has been exegeted. Amillennialists are unconvinced that the chapter should compel belief in a literal period of penultimate divine triumph, either before or after the Parousia. Liberal theology takes this viewpoint because of its objection to the miraculous character of predictive prophecy and because of its reductionistic approach to biblical inspiration; the book of Revelation loses force because of its alleged disunity, lack of authenticity, or factual unreliability (see, e.g., A. Harnack, EncBrit [11th ed. 1910–1911], XVIII, 461–63; R. H. Charles, Studies in the Apocalypse [1913]; comm on Revelation [2 vols., ICC, 1920]; Lectures on the Apocalypse [1922]; G. R. Berry,  Premillennialism and OT Prediction [1929]; and R. W. McEwen’s “Factors in the Modern Survival of Millennialism” [Diss., University of Chicago, 1933]). “Conservative” amillennialism holds to a symbolical interpretation of Rev. 20, either in the Augustinian manner or along the lines of W. W. Milligan (ExposB): “The saints reign for a thousand years; that is, they are introduced into a state of perfect and glorious victory.” Important orthodox proponents of amillennialism include G. Vos, Teaching, of Jesus Concerning the Kingdom of God and the Church (1903; repr 1951); W. Masselink, Why Thousand Years? (1930); F. E. Hamilton, Basis of Millennial Faith (1942); P. Mauro, The Seventy Weeks (1944); O. T. Allis, Prophecy and the Church (1945); G. L. Murray, Millennial Studies (1948); A. Pieters, Seed of Abraham (1950); L. Berkhof, Kingdom of God (1951); Second Coming of Christ (1953); J. Wilmot, Inspired Principles of Prophetic Interpretation (1967). The difficulty all amillennialisms face is the textual weight of Rev. 20. The admission of liberal amillennialist Salmond concerning this passage is noteworthy: “The figurative interpretation, it must be owned, cannot be made exegetically good even in its most plausible applications … . This remarkable paragraph in John’s Apocalypse speaks of a real millennial reign of Christ on earth together with certain of His saints, which comes in between a first resurrection and the final judgment” (pp. 441f).

Premillennialism and OT Prediction [1929]; and R. W. McEwen’s “Factors in the Modern Survival of Millennialism” [Diss., University of Chicago, 1933]). “Conservative” amillennialism holds to a symbolical interpretation of Rev. 20, either in the Augustinian manner or along the lines of W. W. Milligan (ExposB): “The saints reign for a thousand years; that is, they are introduced into a state of perfect and glorious victory.” Important orthodox proponents of amillennialism include G. Vos, Teaching, of Jesus Concerning the Kingdom of God and the Church (1903; repr 1951); W. Masselink, Why Thousand Years? (1930); F. E. Hamilton, Basis of Millennial Faith (1942); P. Mauro, The Seventy Weeks (1944); O. T. Allis, Prophecy and the Church (1945); G. L. Murray, Millennial Studies (1948); A. Pieters, Seed of Abraham (1950); L. Berkhof, Kingdom of God (1951); Second Coming of Christ (1953); J. Wilmot, Inspired Principles of Prophetic Interpretation (1967). The difficulty all amillennialisms face is the textual weight of Rev. 20. The admission of liberal amillennialist Salmond concerning this passage is noteworthy: “The figurative interpretation, it must be owned, cannot be made exegetically good even in its most plausible applications … . This remarkable paragraph in John’s Apocalypse speaks of a real millennial reign of Christ on earth together with certain of His saints, which comes in between a first resurrection and the final judgment” (pp. 441f).

|

|

|

Postmillennial Progress. Postmillennialism of both a “conservative” and a “liberal” type is likewise to be found in the Church. Orthodox advocates of this position (among the best: P. Fairbairn, Interpretation of Prophecy [1865]; Hodge, Shedd, and Strong, in their systematic theologies; B. B. Warfield, Biblical Doctrines [1929]; J. M. Kik, Revelation Twenty [1955]; L. Boettner, The Millennium [1958]) interpret Rev. 20 less symbolically than do the amillennialists (a period of divinely ordained blessedness will in fact precede the end), but nonliteral force is given to the details of the chapter (no de facto resurrection of martyrs or physical presence of Christ on earth is anticipated during the millennial period). Rather, God’s immanent power will be more fully manifest over His enemies as the time of Christ’s return draws closer. Boettner argues, “We do not understand how anyone can take a long range view of history and deny that across the centuries there has been and continues to be great progress, and that the trend is definitely toward a better world” (p. 136).

|

|

|

This is precisely the opinion of “liberal” postmillennialists—but their confidence stems from a different quarter: the eighteenth-century optimistic view of man as basically good and the nineteenth-century “myth of progress.” Thus the old modernism found premillennialism abhorrent because “the world is found to be growing constantly better” (S. J. Case, The Millennial Hope [1918], p. 238) and “the clear vision of present-day prophets … in religion, in philosophy, and in business, revels in a growing future of blessedness for mankind” (G. P. Mains, Premillennialism [1920], p. 107). Unchastened by two world wars, the new secular theology endeavors to revivify nineteenth-century motifs along much the same lines, e.g., with its view of an immanent Christ more and more fully manifested in the social movements of our day. (For critique see J. W. Montgomery, Suicide of Christian Theology [1970].) Protestant “process theology” (J. B. Cobb, Jr., S. Ogden, N. Pittenger) sees man dynamically growing into God. Roman Catholic evolutionary theologian Teilhard de Chardin glimpses God “up ahead” where human history will be fully divinized at a Christic “Omega Point” (cf. Schillebeeckx, God the Future of Man [1968]; J. W. Montgomery, Ecumenicity, Evangelicals and Rome [1969]). Moltmann’s “theology of hope,” in part dependent on Ernst Bloch’s dialectic humanism, has similar affinities with postmillennial confidence in the future of the human drama.

Critics of postmillennialism, whether of the conservative or of the liberal variety, argue that neither the Bible nor human history offers ground for assuming that the human situation is in process of continual amelioration; indeed, because of humanity’s sinful condition, the reverse would appear to be the case. And “if world history is not a movement of progress but rather tends to an increasing concentration of anti-christian power, then the second advent of Jesus for which the Church is praying is not a direct continuation and completion of world history but an event that comes from an entirely different dimension, that suddenly breaks off the preceding development and throws the whole constitution of the present world off its hinges” (K. Heim, Jesus the World’s Perfecter [1961], p. 189).

|

|

|

Premillennial Philosophy of History. Premillennialism endeavors to offer as literal an interpretation of Rev. 20 as possible (Christ will physically return to a world under the sway of the antichrist, defeat him, and with the resurrected saints rule on earth a thousand years; the ultimate destruction of Satanic power will then occur and “God shall be all in all”). Naturally, such an eschatology is anathema to the liberal theological community, so premillennialism is a phenomenon to be observed today only among those holding a strong doctrine of biblical inspiration. The major differences among contemporary premillennialists do not touch the above points, but have to do with whether the millennium ought to be integrated into a dispensational view of Scripture, and whether the “lifting up” of the Church spoken of in 1 Thess. 4:17 occurs before, during, or after the great antichristic tribulation (“pretribulation rapture,” as supported by E. S. English, Re-Thinking the Rapture [1954], v “midtribulation rapture,” as argued by N. B. Harrison, The End [1941], v “posttribulation rapture,” as maintained by N. S. McPherson, Triumph Through Tribulation [1944]). Without any attempt to classify according to these differences, we can list the most important modern supporters of the premillennial position: Alf.; F. Godet, Studies on the NT (1873); E. R. Craven, comm on Revelation (Lange, 1874); N. West, The Thousand Years (1880); Peters; S. P. Tregelles, Hope of Christ’s Second Coming (1886); J. A. Seiss, The Last Times (1878); Lectures on the Apocalypse (1900); W. E. Blackstone, Jesus is Coming (1908); A. Reese, Approaching Advent of Christ (1917); T. Zahn, intro to the NT (1909); comm on Revelation (KEK, 1926); A. C. Gaebelein, Return of the Lord (1925); H. A. Ironside, Lamp of Prophecy (1940); L. S. Chafer, Systematic Theology (1948); G. E. Ladd, Crucial Questions about the Kingdom of God (1952); The Blessed Hope (1956); C. C. Ryrie, Basis of Premillennial Faith (1953); Culver; C. L. Feinberg, Premillennialism or Amillennialism? (1954); J. D. Pentecost, Things to Come (1958); J. F. Walvoord, Millennial Kingdom (1959): M. C. Tenney, “Importance and Exegesis of Rev. 20:1–8,” in J. F. Walvoord, ed., Truth for Today (1963).

The arguments for premillennialism are generally of two types: exegetical and doctrinal. Exegetically, the claim is made that only a literal interpretation of Rev. 20 fulfills the basic hermeneutic rule that a passage of Scripture must be taken in its natural sense unless contextual considerations force a nonliteral rendering. (The burden of proof thus falls upon the opponent of premillennialism to show that such considerations do in fact exist.) Doctrinally, the premillennialist argues that the vindication of God’s ways to humanity entails Christ’s victory and reign in the very sphere in which Satanic power has so long been manifest. For God’s will to be done “on earth as it is in heaven” demands what T. A. Kantonen has so effectively termed “the harvest of history” (The Christian Hope [1954], pp. 65–70; cf. Peters, III, 427–442; and A. J. McClain, Greatness of the Kingdom [1959], pp. 527–531). A. Saphir asked, “Is earth simply a failure, abandoned by God to the power of the enemy, the scene of divine judgment, and not the scene of the vindication and triumph of righteousness?” (Lectures on the Lord’s Prayer [1870]). Perhaps the best statement of the case remains that of Irenaeus (Adv. haer. v.32.1) at the end of the 2nd cent.: “It behooves the righteous first to receive the promise of the inheritance which God promised to the fathers, and to reign in it when they rise again to behold God in this creation which is renovated, and that the judgment should take place afterwards. For it is just that in that very creation in which they toiled or were afflicted, being proved in every way by suffering, they should receive the reward of their suffering; and that in the creation in which they were slain because of their love to God, in that they should be revived again; and that in the creation in which they endured servitude, in that they should reign. For God is rich in all things and all things are his. It is fitting, therefore, that the creation itself, being restored to its primeval condition, should be without restraint under the dominion of the righteous” (ANF translation).[2]

The arguments for premillennialism are generally of two types: exegetical and doctrinal. Exegetically, the claim is made that only a literal interpretation of Rev. 20 fulfills the basic hermeneutic rule that a passage of Scripture must be taken in its natural sense unless contextual considerations force a nonliteral rendering. (The burden of proof thus falls upon the opponent of premillennialism to show that such considerations do in fact exist.) Doctrinally, the premillennialist argues that the vindication of God’s ways to humanity entails Christ’s victory and reign in the very sphere in which Satanic power has so long been manifest. For God’s will to be done “on earth as it is in heaven” demands what T. A. Kantonen has so effectively termed “the harvest of history” (The Christian Hope [1954], pp. 65–70; cf. Peters, III, 427–442; and A. J. McClain, Greatness of the Kingdom [1959], pp. 527–531). A. Saphir asked, “Is earth simply a failure, abandoned by God to the power of the enemy, the scene of divine judgment, and not the scene of the vindication and triumph of righteousness?” (Lectures on the Lord’s Prayer [1870]). Perhaps the best statement of the case remains that of Irenaeus (Adv. haer. v.32.1) at the end of the 2nd cent.: “It behooves the righteous first to receive the promise of the inheritance which God promised to the fathers, and to reign in it when they rise again to behold God in this creation which is renovated, and that the judgment should take place afterwards. For it is just that in that very creation in which they toiled or were afflicted, being proved in every way by suffering, they should receive the reward of their suffering; and that in the creation in which they were slain because of their love to God, in that they should be revived again; and that in the creation in which they endured servitude, in that they should reign. For God is rich in all things and all things are his. It is fitting, therefore, that the creation itself, being restored to its primeval condition, should be without restraint under the dominion of the righteous” (ANF translation).[2]

By John Warwick Montgomery

Amillennialism

Amillenarism or amillennialism is a type of chillegorism that teaches and believes there will be no millennial reign of the righteous on Earth. Amillennialists interpret the thousand years symbolically to refer either to a temporary bliss of souls in heaven before the general resurrection or to the infinite bliss of the righteous after the general resurrection.

This view in Christian eschatology does not hold that Jesus Christ will physically reign on the Earth for exactly 1,000 years. This view contrasts with some postmillennial interpretations and with premillennial interpretations of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation.

The amillennial view regards the “thousand years” mentioned in Revelation 20 as a symbolic number, not as a literal description; amillennialists hold that the millennium has already begun and is simultaneous with the current church age. Amillennialism holds that while Christ’s reign during the millennium is spiritual in nature, at the end of the church age, Christ will return in final judgment and establish a permanent reign in the new heaven and new Earth.

Many proponents dislike the term “amillennialism” because it emphasizes their differences with premillennialism rather than their beliefs about the millennium. “Amillennial” was actually coined in a pejorative way by those who hold premillennial views. Some proponents also prefer alternate names such as nunc-millennialism (that is, now-millennialism) or realized millennialism, although these other names have achieved only limited acceptance and usage.

|

|

|

Variations

There are two main variations of amillennianism, perfect amillenarism (the first resurrection has already happened) and imperfect amillenarism (the first resurrection will happen simultaneously with the second one). The common denominator for all amillenaristic views is the denial of the Kingdom of the righteous on Earth before the general resurrection.

Perfect Amillenarism

- Marcion (c. 85 – 160) taught that only souls will resurrect, rejecting the bodily resurrection. He followed the teachings of Simon Magus (1st century) and Cerdo (1st-2nd centuries) [See. St. Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies, 1, 27; St. Epiphanius of Cyprus, Panarion. Against the Marcionites, Heresies 22 and 42].

- Origen (c. 185 – 254) further developed the amillenarism of Marcion in his teaching about the reign of the saints in heaven while rejecting the idea of the Kingdom of the righteous coming down to the Earth [On the First Principles, book 2, chapter 11; Against Celsus, book 2, chapter 5]. This teaching was later supported by Gaius of Rome (died c. 217) [See Eusebius], St. Dionysius of Alexandria (died 265) [See Eusebius], and Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 263 – 340) [Church History, volume 3, chapter 28; volume 7, chapters 24-25].

- Emanuel Swedenborg (1688 – 1772) taught about the reign of saints in heaven but denied the bodily resurrection [The Open Apocalypse, chapter 20].

- In A.P. Lopukhin’s Explanatory Bible (1904 – 1913), the first resurrection refers to the state of the righteous souls reigning in heaven, that is, “they can be guides and helpers to the Christians who are still fighting the good fight of faith on the earth. The souls find in this a new source of joy and blessing” [Rev 20:4-5].

- Sickenberger (20th century) interprets the first resurrection as the ascension of the souls of martyrs into heaven. The Millennium is for him “a symbolic number”.

- Giblin (20th century), Tadros Malaty (20th century) see the Millennium as the life of saints in heaven.

- Daniil Sysoev, a priest (1974 – 2009), taught that the first resurrection is the life and reign of the righteous souls in heaven [Conversations on the Apocalypse, chapter 20].

|

|

|

Imperfect Amillenarism

- Cerinthus (1st-2nd centuries) believed that Jesus Christ “has not yet risen but will rise when the general resurrection of the dead takes place” [See St. Epiphanius of Cyprus, Panarion, Against Cerinthians, or Merinthians, Heresies 8 and 28, §6], i.e., he denied the first resurrection. At the same time, he also said something quite different: “Jesus suffered and rose from the dead, but Christ, who had descended upon Him, went up to heaven without suffering. And the one who came down from heaven in the form of a dove is Christ, but Jesus is not Christ” [ibid., §1; St. Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies, book 1, chapter 26].

- St. Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306 – 373) believed that the first resurrection would occur simultaneously with the second and both would constitute “one resurrection”. The Millennium signifies “the immensity of eternal life” [Discourse 96. On repentance].

- Blessed Theodoret of Cyrus (386 – 457) expressed similar views on the Millennium to those of St. Ephrem’s. [A Brief Exposition of Divine Dogmas, chapter 21].

- Kraft (20th century) describes the first resurrection as the resurrection of the martyrs and sees the second one as the judgment over all the dead, which basically means that he denies the Millennium.

|

|

|

Teaching

Amillennialism rejects the idea of a future millennium in which Christ will reign on Earth prior to the eternal state beginning but holds:

- that Jesus is presently reigning from heaven, seated at the right hand of God the Father,

- that Jesus also is and will remain with the church until the end of the world, as he promised at the Ascension,

- that the millennium began with the resurrection of Jesus, the first resurrection (Colossians 1:18 [Jesus Christ] is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence; Revelation 20:4-6 [the millennium] is the first resurrection)

- that at Pentecost (or days earlier, at the Ascension), the millennium began, citing Acts 2:16-21, where Peter quotes Joel 2:28-32 on the coming of the kingdom, to explain what is happening,

- and that, therefore the Church and its spread of the good news is indeed Christ’s Kingdom and forever will be.

Amillennialists also cite scripture references to the kingdom not being a physical realm:

- Matthew 12:28, where Jesus cites his driving out of demons as evidence that the kingdom of God had come upon them

- Luke 17:20–21, where Jesus warns that the coming of the kingdom of God can not be observed, and that it is among them

- Romans 14:17, where Paul speaks of the kingdom of God being in terms of the Christians’ actions

Amillennialism also teaches that the binding of Satan, described in Revelation, has already occurred; he has been prevented from “deceiving the nations” by the spread of the gospel.[citation needed] Nonetheless, good and evil will remain mixed in strength throughout history and even in the church, according to the amillennial understanding of the Parable of the Wheat and Tares.

Amillennialism is sometimes associated with Idealism, as both schools teach a symbolic interpretation of many of the prophecies of the Bible and especially of the Book of Revelation. However, many amillennialists do believe in the literal fulfillment of Biblical prophecies; they simply disagree with Millennialists about how or when these prophecies will be fulfilled.

|

|

|

History

Early Church

Few early Christians wrote about this aspect of eschatology during the first century of Christianity, but most of the available writings from the period reflect a millenarianist perspective (sometimes referred to as chiliasm). Bishop Papias of Hierapolis (A.D. 70–155) speaks in favor of a pre-millennial position in volume three of his five volume work and Aristion[when?] and the elder John echoed his sentiments, as did other first-hand disciples and secondary followers. Though most writings of the time tend to favor a millennial perspective, the amillennial position may have also been present in this early period, as suggested in the Epistle of Barnabas, and it would become the ascendant view during the next two centuries. Church fathers of the third century who rejected the millennium included Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215), Origen (184/185 – 253/254), and Cyprian (c. 200 – 258). Justin Martyr (died 165), who had chiliastic tendencies in his theology, mentions differing views in his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, chapter 80:

“I and many others are of this opinion [premillennialism], and [believe] that such will take place, as you assuredly are aware; but, on the other hand, I signified to you that many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.”

Certain amillennialists such as Albertus Pieters understand Pseudo-Barnabas to be amillennial, though many understand it instead to be premillennial. In the 2nd century, the Alogi (those who rejected all of John’s writings) were amillennial, as was Caius in the first quarter of the 3rd century. With the influence of Neo-Platonism and dualism, Clement of Alexandria and Origen denied premillennialism. Likewise, Dionysius of Alexandria (died 264) argued that Revelation was not written by John and could not be interpreted literally; he was amillennial.

Origen’s idealizing tendency to consider only the spiritual as real (which was fundamental to his entire system) led him to combat the “rude” or “crude” Chiliasm of a physical and sensual beyond.

Premillennialism appeared in the available writings of the early church, but it was evident that both views existed side by side. However, the early church fathers’ premillennial beliefs are quite different from the dominant form of modern-day premillennialism, namely dispensational premillennialism.

|

|

|

It is the conclusion of this thesis that Dr. Ryrie’s statement [that dispensationalism was the view of the early church fathers] is historically invalid within the chronological framework of this thesis. The reasons for this conclusion are as follows: (1) the writers/writings surveyed did not generally adopt a consistently applied literal interpretation; (2) they did not generally distinguish between the Church and Israel; (3) there is no evidence that they generally held to a dispensational view of revealed history; (4) although Papias and Justin Martyr did believe in a Millennial kingdom, the 1,000 years is the only basic similarity with the modern system (in fact, they and dispensational pre-millennialism radically differ on the basis of the Millennium); (5) they had no concept of imminency or of a pre-tribulational Rapture of the Church; (6) in general, their eschatological chronology is not synonymous with that of the modern system. Indeed, this thesis would conclude that the eschatological beliefs of the period studied would be generally inimical to those of the modern system (perhaps, seminal amillennialism, and not nascent dispensational premillennialism ought to be seen in the eschatology of the period).

Medieval and Reformation Periods

Amillennialism gained ground after Christianity became a legal religion. It was systematized by St. Augustine in the 4th century, and this systematization carried amillennialism over as the dominant eschatology of the Medieval and Reformation periods. Augustine was originally a premillennialist, but he retracted that view, claiming the doctrine was carnal.

Amillennialism was the dominant view of the Protestant Reformers. The Lutheran Church formally rejected chiliasm in The Augsburg Confession—”Art. XVII., condemns the Anabaptists (of Munster—historically most Anabaptist groups were amillennial) and others ‘who now scatter Jewish opinions that, before the resurrection of the dead, the godly shall occupy the kingdom of the world, the wicked being everywhere suppressed.’” Likewise, the Swiss Reformer Heinrich Bullinger wrote up the Second Helvetic Confession, which reads “We also reject the Jewish dream of a millennium, or golden age on earth, before the last judgment.” John Calvin wrote in Institutes that chiliasm is a “fiction” that is “too childish either to need or to be worth a refutation.” He interpreted the thousand-year period of Revelation 20 non-literally, applying it to the “various disturbances that awaited the church, while still toiling on earth.”

|

|

|

Modern times

Amillennialism has been widely held in the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Churches and the Roman Catholic Church, which generally embraces an Augustinian eschatology and has deemed that premillennialism “cannot safely be taught.” Amillennialism is also common among Protestant denominations such as the Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, Methodist and many Messianic Jews. It represents the historical position of the Amish, Old Order Mennonite, and Conservative Mennonites (though among the more modern groups, premillennialism has made inroads). It is common among groups arising from the 19th century American Restoration Movement such as the Churches of Christ,: 125 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and Christian Churches and Churches of Christ. It also has a following amongst Baptist denominations such as The Association of Grace Baptist Churches in England. Partial preterism is sometimes a component of amillennial hermeneutics. Amillennialism declined in Protestant circles with the rise of Postmillennialism and the resurgence of Premillennialism in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it has regained prominence in the West after World War II.

|

|

|

Postmillennialism

In Christian eschatology (end-times theology), postmillennialism, or postmillenarianism, is an interpretation of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation which sees Christ’s second coming as occurring after (Latin post-) the “Millennium”, a Golden Age in which Christian ethics prosper. The term subsumes several similar views of the end times, and it stands in contrast to premillennialism and, to a lesser extent, amillennialism.

Postmillennialism holds that Jesus Christ establishes his kingdom on earth through his preaching and redemptive work in the first century and that he equips his church with the gospel, empowers the church by the Spirit, and charges the church with the Great Commission (Matt 28:19) to disciple all nations. Postmillennialism expects that eventually the vast majority of people living will be saved. Increasing gospel success will gradually produce a time in history prior to Christ’s return in which faith, righteousness, peace, and prosperity will prevail in the affairs of men and of nations. After an extensive era of such conditions, Jesus Christ will return visibly, bodily, and gloriously to end history with the general resurrection and the final judgment, after which the eternal order follows.

Postmillennialism was a dominant theological belief among American Protestants who promoted reform movements in the 1850s abolitionism and the Social Gospel. Postmillennialism has become one of the key tenets of a movement known as Christian Reconstructionism. It has been criticized by 20th century religious conservatives as an attempt to immanentize the eschaton.

|

|

|

Background

The Savoy Declaration of 1658 contains one of the earliest creedal statements of a postmillennial eschatology:

As the Lord in his care and love towards his Church, hath in his infinite wise providence exercised it with great variety in all ages, for the good of them that love him, and his own glory; so according to his promise, we expect that in the latter days, antichrist being destroyed, the Jews called, and the adversaries of the kingdom of his dear Son broken, the churches of Christ being enlarged, and edified through a free and plentiful communication of light and grace, shall enjoy in this world a more quiet, peaceable and glorious condition than they have enjoyed.

John Jefferson Davis notes that the postmillennial outlook was articulated by men like John Owen in the 17th century, Jonathan Edwards in the 18th century, and Charles Hodge in the 19th century. Davis argues that it was the dominant view in the nineteenth century but was eclipsed by the other millennial positions by the end of World War I due to the “pessimism and disillusionment engendered by wartime conditions.”

Reforms

George M. Fredrickson argues, “The belief that a religious revival and the resulting improvement in human faith and morals would eventually usher in a thousand years of peace and justice antecedent to the Second Coming of Christ was an impetus to the promotion of Progressive reforms, as historians have frequently pointed out.” During the Second Great Awakening of the 1830s, some divines expected the millennium to arrive in a few years. By the 1840s, however, the great day had receded to the distant future, and post-millennialism became the religious dimension of the broader American middle-class ideology of steady moral and material progress.

|

|

|

Key ideas

Although some postmillennialists hold to a literal millennium of 1,000 years, other postmillennialists see the thousand years more as a figurative term for a long period of time (similar in that respect to amillennialism). Among those holding to a non-literal “millennium” it is usually understood to have already begun, which implies a less obvious and less dramatic kind of millennium than that typically envisioned by premillennialists, as well as a more unexpected return of Christ.

Postmillennialism also teaches that the forces of Satan will gradually be defeated by the expansion of the Kingdom of God throughout history up until the second coming of Christ. This belief that good will gradually triumph over evil has led proponents of postmillennialism to label themselves “optimillennialists” in contrast to “pessimillennial” premillennialists and amillennialists.

Many postmillennialists also adopt some form of preterism, which holds that many of the end times prophecies in the Bible have already been fulfilled. Several key postmillennialists, however, did not adopt preterism with respect to the Book of Revelation, among them B. B. Warfield and Francis Nigel Lee.

Other postmillennialists hold to the idealist position of Revelation. The book titled An A-to-Z Guide to Biblical Prophecy and the End Times defines Idealism as “A symbolic description of the on going battle between God and evil.” Those who hold to this view include: R. J. Rushdoony and P. Andrew Sandlin.

Types

Difference in extent

Postmillennialists diverge on the extent of the gospel’s conquest. The majority of postmillennialists do believe in an apostasy, and like B. B. Warfield, believe the apostasy refers to the Jewish people’s rejection of Christianity either during the first century or possibly until the return of Christ at the end of the millennium. This postmillennial perspective essentially dovetails with the thinking of amillennial and premillennial schools of eschatology.

There is a minority of postmillennial scholars, however, who discount the idea of a final apostasy, regarding the gospel conquest ignited by the Great Commission to be total and absolute, such that no unsaved individuals will remain after the Spirit has been fully poured out on all flesh. This minority school, promoted by B. B. Warfield and supported by exegetical work of H.A.W. Meyer, has started to gain more ground, even altering the thinking of some postmillennialists previously in the majority camp, such as Loraine Boettner and R. J. Rushdoony.

|

|

|

The appeal of the minority position, apart from its obvious gambit of taking key scriptures literally (John 12:32; Romans 11:25–26; Hebrews 10:13; Isaiah 2:4; 9:7; etc.), was voiced by Boettner himself after his shift in position: the majority-form of postmillennialism lacks a capstone, which Warfield’s version does not fail to provide. Warfield also linked his views to an unusual understanding of Matthew 5:18, premised on Meyer’s exegesis of the same passage, which presupposed a global conquest of the gospel in order for the supposed prophecy in that verse to be realized, which inexorably leads to a literal fulfillment of the third petition of the Lord’s Prayer: “Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven.”

John Calvin’s exposition of that part of the Lord’s Prayer all but adopts the minority postmillennial position but Calvin, and later Charles Spurgeon, were remarkably inconsistent on eschatological matters. Spurgeon delivered a sermon on Psalm 72 explicitly defending the form of absolute postmillennialism held by the minority camp today, but on other occasions he defended premillennialism. Moreover, given the nature of Warfield’s views, Warfield disdained the millennial labels, preferring the term “eschatological universalism” for the brand of postmillennialism now associated with his thinking.

Like those who follow in his footsteps, Warfield did not seek to support his doctrine of cosmic eschatology from Revelation 20, treating that passage (following Kliefoth, Duesterdieck, and Milligan) as descriptive of the intermediate state and the contrast between church militant and triumphant. This tactic represented an abandonment of the Augustinian approach to the passage, ostensibly justified by a perceived advance in taking the Book of Revelation’s parallel passages to the little season of Satan more seriously (cf. Revelation 6:11 and 12:12).

|

|

|

Difference in Means

Postmillennialists also diverge on the means of the gospel’s conquest. Revivalist postmillennialism is a form of the doctrine held by the Puritans and some today that teaches that the millennium will come about not from Christians changing society from the top down (that is, through its political and legal institutions) but from the bottom up at the grassroots level (that is, through changing people’s hearts and minds).

Reconstructionist postmillennialism, on the other hand, sees that along with grassroots preaching of the Gospel and explicitly Christian education, Christians should also set about changing society’s legal and political institutions in accordance with Biblical, and also sometimes Theonomic, ethics (see Dominion theology). The revivalists deny that the same legal and political rules which applied to theocratic state of Ancient Israel should apply directly to modern societies, which are no longer directly ruled by Israel’s prophets, priests, and kings. In the United States, the most prominent and organized forms of postmillennialism are based on Christian Reconstructionism and hold to a reconstructionist form of postmillennialism advanced by R.J. Rushdoony, Gary North, Kenneth Gentry, and Greg Bahnsen.

|

|

|

Premillennialism

Premillennialism, in Christian eschatology, is the belief that Jesus will physically return to the Earth (the Second Coming) before the Millennium, a literal thousand-year golden age of peace. Premillennialism is based upon a literal interpretation of Revelation 20:1–6 in the New Testament, which describes Jesus’s reign in a period of a thousand years.

Denominations such as Oriental Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Anglicanism, and Lutheranism are generally amillennial and interpret Revelation 20:1–6 as pertaining to the present time, a belief that Christ currently reigns in Heaven with the departed saints; such an interpretation views the symbolism of Revelation as referring to a spiritual conflict between Heaven and Hell rather than a physical conflict on Earth. Amillennialists do not view the millennium mentioned in Revelation as pertaining to a literal thousand years, but rather as symbolic, and see the kingdom of Christ as already present in the church beginning with the Pentecost in the book of Acts.

Premillennialism is often used to refer specifically to those who adhere to the beliefs in an earthly millennial reign of Christ as well as a rapture of the faithful coming before (dispensational) or after (historic) the Great Tribulation preceding the Millennium. For the last century, the belief has been common in Evangelicalism according to surveys on this topic. Amillennialists do not view the thousand years mentioned in Revelation as a literal thousand years but see the number “thousand” as symbolic and numerological.

Premillennialism is distinct from the other views such as postmillennialism which views the millennial rule as occurring before the second coming.

|

|

|

Terminology

The current religious term “premillennialism” did not come into use until the mid-19th century. Coining the word was “almost entirely the work of British and American Protestants and was prompted by their belief that the French and American Revolutions (the French, especially) realized prophecies made in the books of Daniel and Revelation.”

Other views

The proponents of amillennialism interpret the millennium as being a symbolic period of time, which is consistent with the highly symbolic nature of the literary and apocalyptic genre of the Book of Revelation, sometimes indicating that the thousand years represent God’s rule over his creation or the Church.

Post-millennialism, for example, agrees with premillennialism about the future earthly reign of Christ, but disagrees on the concept of a rapture and tribulation before the millennium begins. Postmillennialists hold to the view that the Second Coming will happen after the millennium.

|

|

|

History

Justin Martyr and Irenaeus

Justin Martyr, in the 2nd century was one of the first Christian writers to clearly describe himself as continuing in the “Jewish” belief of a temporary messianic kingdom before the eternal state. However, the notion of Millennium in his Dialogue with Trypho seem to differ from that of the Apology. According to Johannes Quasten, “In his eschatological ideas Justin shares the views of the Chiliasts concerning the millennium.” He maintains a premillennial distinction, namely that there would be two resurrections, one of believers before Jesus’ reign and then a general resurrection afterward. Justin wrote in chapter 80 of his work Dialogue with Trypho, “I and others who are right-minded Christians on all points are assured that there will be a resurrection of the dead, and a thousand years in Jerusalem, which will then be built… For Isaiah spoke in that manner concerning this period of a thousand years.” Though he conceded earlier in the same chapter that his view was not universal by saying that he “and many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.”

Irenaeus, the late 2nd century bishop of Lyon, was an outspoken premillennialist. He is best known for his voluminous tome written against the 2nd century Gnostic threat, commonly called Against Heresies. In the fifth book of Against Heresies, Irenaeus concentrates primarily on eschatology. In one passage, he defends premillennialism by arguing that a future earthly kingdom is necessary because of God’s promise to Abraham, he wrote “The promise remains steadfast… God promised him the inheritance of the land. Yet, Abraham did not receive it during all the time of his journey there. Accordingly, it must be that Abraham, together with his seed (that is, those who fear God and believe in Him), will receive it at the resurrection of the just.” In another place Irenaeus also explained that the blessing to Jacob “belongs unquestionably to the times of the kingdom when the righteous will bear rule, after their rising from the dead. It is also the time when the creation will bear fruit with an abundance of all kinds of food, having been renovated and set free… And all of the animals will feed on the vegetation of the earth… and they will be in perfect submission to man. And these things are borne witness to in the fourth book of the writings of Papias, the hearer of John, and a companion of Polycarp.” (5.33.3) Apparently, Irenaeus also held to the sexta-/septamillennial scheme writing that the end of human history will occur after the 6,000th year. (5.28.3)

|

|

|

Other ante-Nicene Premillennialists

Irenaeus and Justin represent two of the most outspoken premillennialists of the pre-Nicean church. Other early premillennialists included Pseudo-Barnabas, Papias, Methodius, Lactantius, Commodianus Theophilus, Tertullian, Melito, Hippolytus of Rome, Victorinus of Pettau and various Gnostics groups and the Montanists. Many of these theologians and others in the early church expressed their belief in premillennialism through their acceptance of the sexta-septamillennial tradition. This belief claims that human history will continue for 6,000 years and then will enjoy Sabbath for 1,000 years (the millennial kingdom), thus all of human history will have a total of 7,000 years prior to the new creation.

Ante-Nicene opposition

The first clear opponent of premillennialism associated with Christianity was Marcion. Marcion opposed the use of the Old Testament and most books of the New Testament that were not written by the apostle Paul. Regarding Marcion and premillennialism, Harvard scholar H. Brown noted,

The first great heretic broke drastically with the faith of the early church in abandoning the doctrine of the imminent, personal return of Christ…Marcion did not believe in a real incarnation, and consequently there was no logical place in his system for a real Second Coming…Marcion expected the majority of mankind to be lost…he denied the validity of the Old Testament and its Law…As the first great heretic, Marcion developed and perfected his heterodox system before orthodoxy had fully defined itself…Marcion represents a movement that so radically transformed the Christian doctrine of God and Christ that it can hardly be said to be Christian.

Throughout the Patristic period—particularly in the 3rd century—there had been rising opposition to premillennialism. Origen was the first to challenge the doctrine openly. Through allegorical interpretation, he had been a proponent of amillennialism (of course, the sexta-septamillennial tradition was itself based upon similar means of allegorical interpretation). Although Origen was not always wholly “orthodox” in his theology, he had at one point completely spiritualized Christ’s second coming prophesied in the New Testament. Origen did this in his Commentary on Matthew when he taught that “Christ’s return signifies His disclosure of Himself and His deity to all humanity in such a way that all might partake of His glory to the degree that each individual’s actions warrant (Commentary on Matthew 12.30).” Even Origen’s milder forms of this teaching left no room for a literal millennium and it was so extreme that few actually followed it. But his influence did gain wider acceptance especially in the period following Constantine.

|

|

|

Dionysius of Alexandria stood against premillennialism when the chiliastic work, The Refutation of the Allegorizers written by Nepos, a bishop in Egypt became popular in Alexandria. Dionysius argued against Nepos’s influence and convinced the churches of the region of amillennialism. The church historian, Eusebius, reports this in his Ecclesiastical History. Eusebius also had low regard for the chiliast, Papias, and he let it be known that, in his opinion, Papias was “a man of small mental capacity” because he had taken the Apocalypse literally.

Middle Ages and the Reformation