Please Help Us Keep These Thousands of Blog Posts Growing and Free for All

$5.00

|

|

|

Introduction to the Syriac Peshitta

The Syriac Peshitta stands as one of the most important early versions of the Bible, offering a vital window into the textual transmission of both Old and New Testament Scriptures. The term Peshitta (ܦܫܝܛܬܐ in Syriac) means “simple,” “common,” or “straightforward,” which accurately characterizes the version’s intent: to provide a clear, accessible rendering of Scripture for the Syriac-speaking Christian community. This community, primarily located in Edessa and other areas of the ancient Near East, needed the Scriptures in their own language, just as Latin-speaking Christians had the Old Latin and Egyptian Christians had Coptic translations. By the fourth century C.E., the Peshitta had become the standard biblical text for the Syriac-speaking Church and remains foundational to the Syriac Christian tradition to this day.

Language and Historical Context

Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic that developed in Edessa (modern-day Urfa, southeastern Turkey) and became the literary and ecclesiastical language of the Syriac-speaking church. Aramaic itself was the lingua franca across much of the Near East from the time of the Assyrian and Babylonian empires (circa 700s B.C.E.) through the Persian period (539–331 B.C.E.) and remained influential well into the Roman era. By the time of Jesus (born 2 or 1 B.C.E., crucified 33 C.E.), Aramaic was still the spoken language of the Jewish people in Palestine.

As Christianity spread eastward from Antioch into Mesopotamia, the need arose for the Scriptures to be translated from Greek into Syriac for use in liturgical and educational settings. The Syriac Peshitta reflects this historical development and provides a stable, enduring version of the biblical text that was revered and carefully preserved by early Eastern Christians.

|

|

|

The Old Testament Peshitta

The Peshitta Old Testament was not translated from the Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT) but primarily from the Septuagint (LXX) and other earlier Hebrew texts—likely proto-Masoretic or similar to the ones reflected in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Most scholars agree that this translation predates Christianity and was likely produced by Jewish scribes sometime before the first century C.E. However, in its final form, it was adopted and transmitted by Christians.

Although the Old Testament Peshitta shows evidence of harmonization with the Greek Septuagint, it is not a mere translation of the LXX. It represents an independent textual tradition, valuable for comparison with both the MT and the LXX. For example, in Isaiah and the Psalms, the Peshitta frequently aligns with the Hebrew text over against the Greek.

Its rendering is generally literal and conservative. However, it does show some interpretive translation in prophetic and poetic texts, which may have been influenced by Jewish exegetical traditions. The presence of the divine name in the Peshitta Old Testament is represented by the Syriac equivalent for “Lord,” not by the Tetragrammaton (JHVH), reflecting the practice of substituting MarYa (“the Lord”) where the divine name occurred in the Hebrew text.

|

|

|

The New Testament Peshitta

The Syriac Peshitta New Testament was likely produced in the late second to early third century C.E., making it one of the earliest complete vernacular versions of the Christian Greek Scriptures. Its translation from Greek into Syriac was executed with precision and consistency, indicating that it was likely the result of a deliberate ecclesiastical project rather than scattered or individual efforts.

Significantly, the original form of the Peshitta New Testament contained only 22 books—omitting 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, and Revelation. These omissions were not arbitrary; they reflect the incomplete canonization of these texts in the Syriac-speaking churches at the time of translation. These books were added in later revisions, namely the Philoxenian Version (508 C.E.) and the Harclensis Version (616 C.E.).

The text of the Peshitta New Testament generally reflects the Byzantine text-type, though it shows important Alexandrian and some Western influences in certain readings. Its rendering of Christological texts, such as John 1:1 and Philippians 2:6–11, demonstrates a high Christology consistent with early orthodoxy. At the same time, the Peshitta does not contain theological modifications seen in later doctrinally biased translations.

|

|

|

Textual Features of the Peshitta

The translation style of the Peshitta is marked by both accuracy and clarity. It avoids paraphrasing, except in poetic or highly figurative texts, and its vocabulary is generally consistent and theological terms are carefully rendered. This regularity makes it particularly useful in identifying Greek textual variants.

Unlike earlier translations like the Old Syriac Gospels, the Peshitta was not a free or paraphrastic version. It represents a more disciplined translation tradition, and it displays uniformity across manuscripts—suggesting early authoritative oversight or perhaps redaction to establish textual unity within the Syriac-speaking churches.

The Peshitta uses distinctive Syriac terminology for New Testament concepts. For instance, the term for “baptize” is ‘amad, literally “immerse,” which supports a literal understanding of the baptismal practice in the early church. Similarly, terms for “repentance,” “grace,” and “faith” reflect a sound theological and linguistic consistency with the Greek original.

|

|

|

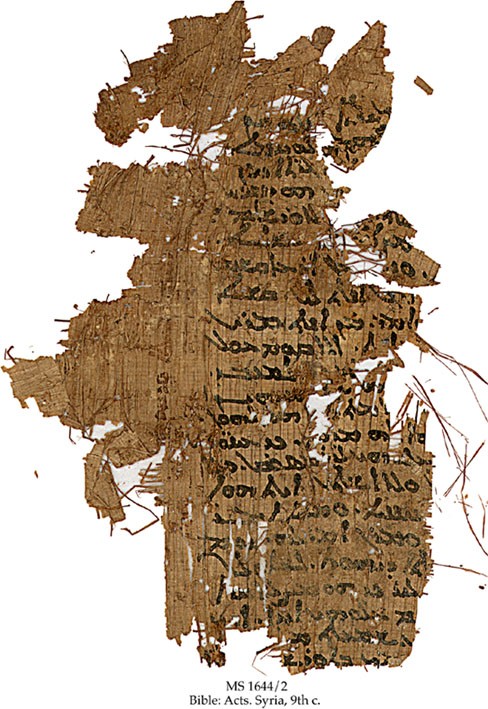

Manuscript Evidence and Early Witnesses

The manuscript tradition of the Peshitta is extensive, with over 350 extant New Testament manuscripts, some dating to the fifth and sixth centuries C.E. Among the most notable are:

Codex Phillipps 1388 (sixth century C.E.): Contains the four Gospels in beautiful Estrangelo script.

Codex Ambrosianus (sixth century C.E.): Preserves both Old and New Testament books and is one of the most important complete Peshitta manuscripts.

The British Library Collection and the Vatican Syriac Manuscripts also house numerous copies of the Peshitta, enabling scholars to establish a stable textual tradition with a high level of agreement.

The uniformity among these manuscripts stands in stark contrast to the diversity seen in the Old Syriac versions, further confirming the ecclesiastical acceptance and authority of the Peshitta text.

|

|

|

Earlier Syriac Translations: The Old Syriac Gospels

Before the Peshitta, there existed two primary Syriac Gospel manuscripts known as the Old Syriac Gospels:

The Curetonian Gospels: Discovered in the 19th century by William Cureton and preserved in the British Library, this fifth-century manuscript preserves an earlier Syriac translation.

The Sinaitic Palimpsest: Found by Agnes Smith Lewis in 1892 at St. Catherine’s Monastery, it dates to the late fourth century and is one of the earliest Syriac witnesses to the four Gospels.

These Old Syriac Gospels reflect a Western text-type and differ considerably from the Peshitta. They exhibit harmonizations, omissions, and paraphrastic renderings that mark them as distinct from the more polished and uniform Peshitta.

For example, in Luke 23:34 (“Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing”), this saying of Jesus is omitted in the Old Syriac manuscripts, aligning them with P75 and Codex Vaticanus (B), whereas the Peshitta includes the verse. Such textual divergences provide vital data points in textual criticism.

|

|

|

Later Revisions: Philoxenian and Harclensis Versions

The Philoxenian Version was commissioned by Philoxenus, Bishop of Mabbug, in 508 C.E. It sought to provide a more literal rendering of the Greek New Testament and included the five previously omitted books. However, it was soon replaced by a more thorough revision.

The Harclensis Version, completed in 616 C.E. by Thomas of Harkel, represents an extreme literalism. It closely follows the Greek word order and syntax, even to the point of awkwardness in Syriac. Marginal notes and Greek transliterations are also included. The Harclensis version was patterned after Origen’s Hexapla in its methodology and exhibits a mixture of Alexandrian and Byzantine readings.

These later revisions serve a dual purpose: they supplement the Peshitta canonically and provide important insights into the Greek textual tradition of the early sixth century. However, their rigid literalism makes them less readable and less influential than the Peshitta.

|

|

|

Theological Implications of the Peshitta

The Peshitta’s translation of key theological texts demonstrates the theological orthodoxy of the Syriac-speaking church. Consider John 1:1 in the Peshitta:

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

This is rendered with no indefinite article, as Syriac lacks the grammatical mechanism for one, maintaining theological consistency with the Greek θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος.

Another example is Philippians 2:6–11, where the Peshitta preserves the pre-existence and divine status of Christ with clarity, maintaining the reading that He “emptied Himself” and “became obedient to death.”

These renderings reflect a high view of Christ’s nature and support the early church’s understanding of His divinity, countering theories that the Peshitta reflects an adoptionist or subordinationist Christology.

|

|

|

The Peshitta in Textual Criticism

From a textual criticism perspective, the Peshitta serves as an indirect but valuable witness to the early Greek text of the New Testament, especially for the second to fifth centuries C.E.. Though it is not superior to the earliest Greek papyri or uncials in terms of primacy, it provides corroborative data where Greek evidence is thin or divided.

Its uniformity, theological precision, and manuscript reliability make it especially useful when evaluating readings in the Alexandrian and Byzantine streams. When the Greek textual tradition diverges—such as in John 1:18, where some manuscripts read “the only begotten God” and others “the only begotten Son”—the Peshitta can offer insight into which reading was prevalent in the Eastern churches.

However, it must be used carefully. Because it is a translation, certain Greek idioms and textual variants are naturally obscured by the process of rendering into Syriac. Therefore, the Peshitta is best used in concert with Greek manuscripts and other early versions like the Latin and Coptic.

|

|

|

Conclusion: Enduring Value of the Peshitta

The Syriac Peshitta remains a key witness in the world of early Bible versions. It reflects the linguistic, ecclesiastical, and theological landscape of Syriac Christianity and preserves a conservative, reliable text of the Scriptures. Along with the Greek, Latin, and Coptic versions, it contributes to the complex and fascinating discipline of New Testament textual criticism.

As the earliest complete vernacular translation of the Bible, it deserves careful study and continued scholarly attention—not only for its value in textual criticism, but also for what it reveals about the faithful transmission of Scripture among early believers.

You May Also Enjoy

How Can Textual Variants Strengthen Our Confidence in the Bible Rather Than Undermine It?