Please Help Us Keep These Thousands of Blog Posts Growing and Free for All

$5.00

The 39 books of the Hebrew Scriptures by some 33+ authors running from Genesis to Malachi were completed about 440 BCE.[1] After the seventy years of exile in Babylon, there was a school of copyists or scribes (Sopherim) that were developed. Ezra wrote, “this Ezra went up from Babylon. And he was a ready scribe in the law of Moses, which Jehovah, the God of Israel, had given; and the king granted him all his request, according to the hand of Jehovah his God upon him.” (Ezra 7:6) Ezra was a skilled copyist. Centuries before the New Testament books were penned; the Hebrew Scriptures were meticulously copied by faithful scribes. These scribes were called Sopherim, from the time of Ezra (c. 460 BCE) until the time of Jesus Christ, a term that was clearly derived from the Hebrew verb “to count.” Why? According to the Talmud, this was because they counted all of the letters of the Law. Can we even imagine the level of dedication it must have taken, the stress, the strain to count every letter? They literally had to count 815,140 Hebrew letters in the Scriptures each time they copied a manuscript. Great care was taken to prevent corruption of the text.

It is true that the later Sopherim (scribe-copyists) would take some liberties with the Hebrew text they were supposed to be copying. However, it was not to the point of altering the message. Moreover, other than some minor scribal errors and a handful of intentional errors the Sopherim and later the Masoretes, proved to be careful, meticulous caretakers of the Hebrew text. The Masoretes were early Jewish scholars, who were the successors to the Sopherim, in the centuries following Christ, who produced what came to be known as the Masoretic text. The Masoretes was well aware of the alterations made by the earlier Sopherim. Rather than simply remove the alterations, they chose to note them in the margins or at the end of the text. These marginal notes came to be known as the Masora.

|

|

|

The Masoretes were very much concerned with the accurate transmission of each word, even each letter, of the text they were copying. Accuracy was of supreme importance; therefore, the Masoretes use the side margins of each page to inform others of deliberate or inadvertent changes in the text by past copyists. The Masoretes also use these marginal notes for other reasons as well, such as unusual word forms and combinations. They even marked how frequent they occurred within a book or even the whole Hebrew Old Testament. Of course, marginal spaces were very limited, so they used an abbreviated code. They formed a cross-checking tool as well, where they would mark the middle word and letter of certain books. As was stated above and deserves to be mentioned again, their push for accuracy moved them to go so far as to count every letter of the Hebrew Old Testament. The material on which these scrolls were penned was perishable. Therefore, there had to by many copies made. Our focus here is on the scribal profession of an even earlier period. Did ancient Israel have skilled copyists?

The Scribal Profession from Early Periods

What about the neighbors of Israel? In Mesopotamia some four thousand years ago, five hundred years before Moses, about the time Abraham was born in Ur of the Chaldeans, historical, religious, legal, scholarly, and literary texts were being authored, published, and circulated. There were prosperous scribal schools in those days that trained scribes how to accurately copy the existing texts. Modern-day scholars of the Ancient Middle East, find few scribal errors in Babylonian texts that had been copied repeatedly for over a thousand years.

Scribal schools and professional scribes were not found in ancient Mesopotamia alone. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East states: “A Babylonian scribe of the mid-second millennium BCE would probably have felt at home in any number of scribal centers throughout Mesopotamia, Syria, Canaan, and even Egypt.”[2]

|

|

|

During Moses’ first forty years of life, he lived in Egypt where the professional scribe enjoyed a special status. The professional scribe was very busy at work copying and recopying works of literature. The work of a scribe is even depicted as decorations on Egyptian tombs that date back to a time before Abraham. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East states: “The evolution of writing in ancient Mesopotamia, and the parallel development of ancient Egyptian scripts and their influence in the contemporary Near East, reflects the growing stature and organization of the scribal class in antiquity. Scribes set the standard and defined literacy in its institutionalized form in the school and at court. By the second millennium BCE, they had created a canon of literature that exemplified the great civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt and established a code of ethics for the professional scribe. (Italics mine) The sum total of their studies, station in society, and literary productivity might aptly be called scribal culture (Oppenheim, 1964, chap. 5; Hallo, 1991).”

The above mentioned “code of ethics” would include the use of colophons that were appended to the main text. “Colophon. from a Greek word for ‘finishing.’ In the context of copying manuscripts, ‘a finishing touch,’ referring to comments that scribes sometimes added at the end of a copy. The comment could be anything but might provide valuable information as to when and where the manuscript was written, [and sometimes the name of the scribe as well as the owner of the text being copied.”[3] These are indications of a professional scribe, which suggest a concern for accuracy.

Professor Alan R. Millard, we quote again at length, states:

These diverse examples of extrabiblical documents reveal how ancient copyists wrote their texts, and how they tried to write them so they would be readily legible to anyone trained in the same conventions. In this atmosphere, too, the early copyists of the Old Testament books were bred. That they maintained similar high standards of careful and accurate copying is proved, at least in certain respects, by the following collection of examples. Within the Old Testament are numerous foreign names, many of them alien to the western Semite. (Foreign names pose problems in all languages and scripts; the various spellings of East European or Oriental names in our newspapers illustrate that.) Where ancient writings of these names are available, detailed study shows the Hebrew writings represent the contemporary forms very closely. Thus, the names of the Assyrian kings Tiglath-pileser and Sargon, as handed down through the Old Testament, turn out to be accurate reflections of the Assyrian dialect forms of these names. Tiglath-pileser is found in an almost identical spelling on the Aramaic Bar- Rakkab stele from Zinjirli, carved during his reign, or very shortly after. Sargon, occurring in Isaiah 20:1, has become familiar in Akkadian dress as Sharru-ken, but in Assyria during the king’s rule, the sh was pronounced s and the k as 9 as in Tiglath-pileser. These are normal sound-shifts between the Babylonian and the Assyrian speaking regions in the early first millennium B.C. They are demonstrated by the way Sargon s name IS spelled In Aramaic letters on two documents. In the Aramaic letter written on a potsherd sent to Ashur, the old Assyrian capital city, from southern Babylonia, Sargon appears as sh, r, k, n, shar-ken, while on the Aramaic seal of one of his officers, known from an impression found at Khorsabad, Sargon’s new city in Assyria, it is s, r, g, n, sar-gon. It is exactly that spelling that has been preserved in the traditional Hebrew text of the Old Testament. A comparable precision can be argued for other foreign names throughout the Old Testament, as continuing study and discoveries indicate. In a recently published papyrus fragment from Elephantine, dated 484 B.C., the name of king Xerxes (Ahasuerus) is seen for the first time written in Aramaic with prosthetic alep as in the Old Testament and in Akkadian. From, the same age there also survives a seal now in the British Museum. According to its Aramaic inscription, this cylinder seal belonged to a Persian, Parshandatha son of Artadatha. Where an identical name is read in Esther 9:7, the likelihood that the Jewish scribes correctly preserved a good Persian name seems high. Now these minutiae may not seem to be of great consequence and may simply show the scribes could transmit names with precision. There is a corollary, however, which deserves emphasis: in each case mentioned, the Septuagint differs considerably from the Hebrew. Sargon, in Isaiah 20:1, became Arna; Parshandatha was distorted through Pharsannestain to become two names, Pharsan and Nestain, in Codex Vaticanus. These cases, not confined to one book, should at least warn against reliance on the Septuagint for emendation of proper names in the Old Testament, unless the evidence against the Hebrew text is very strong indeed.

|

|

|

Indeed, the purpose of this paper is to point to the care which was an integral part of a scribe’s skill in the ancient Near East. The practices of scriptoria in imperial Rome offer a strong contrast, as the complaints of several ancient authors reveal, but the mass production techniques applied there were probably never at home in the world of the Old Testament. Rather, from the examples presented, and from many others, a copying process can be discerned that included checking and correction, a process that had built-in devices to forestall error. Some of these, the counting of lines or words in particular, reemerge in the traditions of the Massoretes in the early Middle Ages. (Italics mine) That device is so obvious that a connection with Babylonian practice is unlikely. It is part of an attitude which was common: the copyist’s task was to reproduce his exemplar as faithfully as possible.[4]

Therefore, we see thus far that long before the time of Moses and Joshua (15th and 14th centuries BCE), even before Abraham (Late 21st century BCE), there existed scribal schools training professional scribes throughout the Ancient Middle East, whose main focus was care and accuracy. The question to be asked now is was the same kind of scribal schools and practices found in Israel? Does the internal evidence in the Bible give us any kind of indication?

|

|

|

Scribes in Ancient Israel

It would be absolutely ridiculous to argue that the Israelites were surrounded by nation after nation with scribal schools that were training professional scribes who held special elite positions within society, for a thousand years before Joshua even entered the Promised Land, and somehow the Israelites were the one nation who had no scribal schools or professional scribes and was incapable of recording their own history. This is simply inconceivable to think, as many historians try to argue, that from the late 16th century to the middle 5th century BCE the Israelites were all illiterate because it was a pastoralist nation. The nation of Israel may have started off as shepherds and farmers, but this does not mean that there were not select individuals who had scribal skills. You cannot paint the entire nation with such a broad brush and then apply it to all individuals. Moreover, it was not long before the nation of Israel had a king and a priesthood, cities, towns, market places, and doing international business. Second, the author of the first five books, Moses, was raised and lived in the Pharaoh’s household for the first forty years of his life, which means he would have learned some scribal skills, such as recording events and compiling itineraries, among other things.[5]

Deuteronomy 1:15 says: “So I [Moses] took the heads of your tribes, wise and experienced men, and set them as heads over you, commanders of thousands, commanders of hundreds, commanders of fifties, commanders of tens, and officers, throughout your tribes.” Some have likely rightly argued that Moses was here referring to, in part, others in ancient Israel who possessed scribal skills. Did Moses appoint officials who were proficiently literate, highly skilled persons, who could understand spoken words, and had an intermediate-advanced level grasp of written words? Did some have the proficient ability to prepare short texts for daily living and employment tasks that require reading skills at the intermediate level? Was these ones literate writers who were trained in writing and could record decisions and order affairs, as well as serve as a copyist or scribe, or even collect a tenth part, or 10 percent from the Israelite people. Who were the officers spoken of in Deuteronomy by Moses?

This Hebrew term referred to (1) a person who was in charge of workers; it also referred to (2) a civil servant, an office holder of some sort or officer in the military. The Hebrew word for “officers” (שֹׁטֵר (šō·ṭēr)) could also refer to (3) a “recorder, scribe, ruling clerk, i.e., an officer in charge of writing and records.”[6] This Hebrew term occurs many times in Bible texts where it was referring to the days of Moses and Joshua. Whether the third use of the word indicates that there was a number of scribes or secretaries in Israel, who carried out extensive responsibilities in the early years of the nation cannot be said with absolute certainty. However, the historical setting and the context strongly suggests such recorders, scribes, and clerks existed and this is only reasonable considering the surrounding nations. It wasn’t like Israel lived in a vacuum.

|

|

|

Books, Reading, and Writing; Literacy

and Early Jewish Education

The priests of Israel (Num. 5:23) and leading persons, such as Moses (Ex. 24:4), Joshua (Josh. 24:26), Samuel (1 Sam 10:25), David (2 Sam. 11:14-15), and Jehu (2 Ki 10:1, 6), were capable of reading and writing. The Israelite people themselves generally could read and write, with few exceptions. (Judges 8:14; Isa. 10:19; 29:12) Even though Deuteronomy 6:8-9 is used figuratively, the command to write the words of the Law on the doorposts of their house and their gates implied that they were literate. Yes, it is true that even though Hebrew written material was fairly common, few Israelite inscriptions have been discovered. One reason for this is that the Israelites did not set up many monuments to admire their accomplishments. Thus, most of the writing, which would include the thirty-nine books of the Bible were primarily done with ink on papyrus or parchment. Most did not survive the damp soil of Palestine. Nevertheless, the Hebrew Old Testament Scriptures were preserved throughout the centuries by careful, meticulous copying and recopying.

During the first seven years of Christianity (29-36 CE), three and a half with Jesus’ ministry and three and a half after his ascension, only Jewish people became disciples of Christ and formed the newly founded Christian congregation. In 36 CE the first gentile was baptized: Cornelius.[7] From that time forward Gentiles came into the Christian congregations. However, the church still consisted mostly of Jewish converts. What do we know of the Jewish family, as far as education? Within the nation of Israel, everyone was strongly encouraged to be literate. The texts of Deuteronomy 6:8-9 and 11:20 were figurative (not to be taken literally). However, we are to ascertain what was meant by the figurative language, and that meaning is what we take literally.

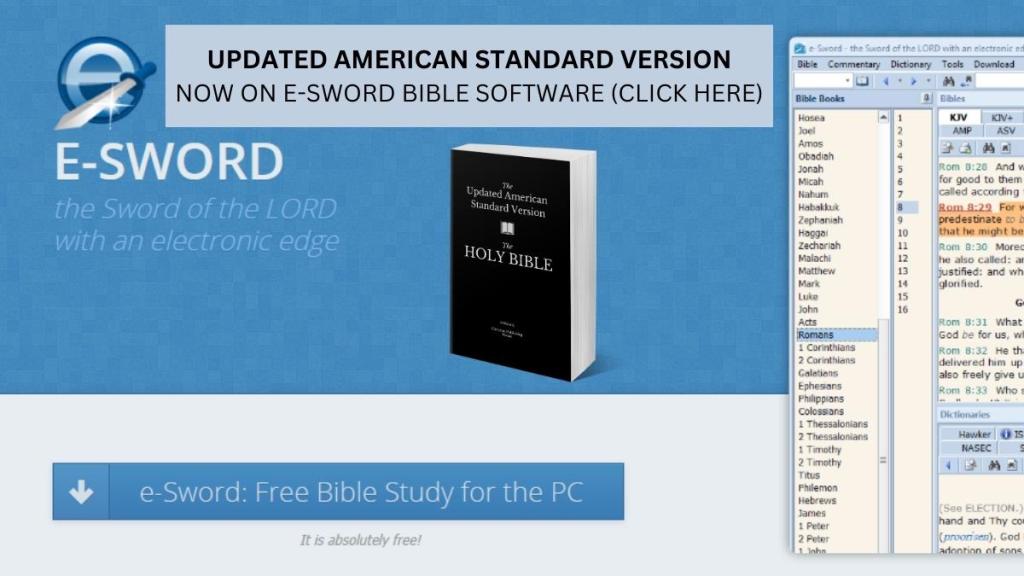

Deuteronomy 6:8-9 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

8 You shall bind them [God’s Word] as a sign on your hand and they shall be as frontlets bands between your eyes.[8] 9 You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.

Deuteronomy 11:20 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

20 You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates,

The command to bind God’s Word “as a sign on your hand,” denoted constant remembrance and attention. The command that the Word of God was “to be as frontlet bands between your eyes,” denoted that the Law should be kept before their eyes always, so that wherever they looked, whatever was before them, they would see the law before them. Therefore, while figurative, these texts implied that Jewish children grew up being taught how to read and to write. The Gezer Calendar (ancient Hebrew writing), dated to the 10th-century BCE, is believed by some scholars to be a schoolboy’s memory exercise.

Take note of how the first copy of the Law was made. In the final months of Moses life, he told the Israelites,

Deuteronomy 27:1-4 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

27 Then Moses and the elders of Israel charged the people, saying, “Keep all the commandments which I command you today. 2 And on the day you cross over the Jordan to the land that Jehovah your God is giving you, you shall set up large stones and coat them with plaster. 3 And you shall write on them all the words of this law, when you cross over to enter the land that Jehovah your God is giving you, a land flowing with milk and honey, as Jehovah, the God of your fathers, has spoken to[9] you. 4 And when you have crossed over the Jordan, you shall set up these stones, concerning which I command you today, on Mount Ebal, and you shall cover them with plaster.

After Joshua and the Israelite army destroyed Jericho and Ai, he had the Israelites gather together at Mount Ebal, which was located in the center of the Promised Land. It was here that Joshua followed through with the command of Moses, “He wrote there on the stones a copy of the law of Moses, which he [Moses] had written.”

Joshua 8:30-32 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

30 Then Joshua built an altar to Jehovah, the God of Israel, on Mount Ebal, 31 just as Moses the servant of Jehovah had commanded the sons of Israel, as it is written in the book of the law of Moses, an altar of uncut stones on which no man had wielded an iron tool; and they offered burnt offerings on it to Jehovah, and sacrificed peace offerings. 32 He wrote there on the stones a copy of the law of Moses, which he[10] had written, in the presence of the sons of Israel.

|

|

|

The Integrity of the Hebrew Text

The copying of the Hebrew Scriptures continued long after the days of Moses and Joshua. As the copies wore out due to the effects of being handled, light, humidity and mold, they were eventually replaced with others. This process went on for centuries. Certainly, the Jewish people were highly interested in the integrity of the Hebrew text. Nevertheless, the copyists were not inspired and moved along with the Holy Spirit like the authors were. Therefore, human error was bound to creep into the text. The question is, did the scribal errors substantially alter the Bible text? No, definitely not, the vast majority of the textual variants were insignificant and had no effect on the integrity of the Hebrew Old Testament, which is evidenced by many centuries of scholars comparing the ancient manuscripts that have come to light.

Around 642 BCE, in the time of King Josiah, Hilkiah, the high priest “found the Book of the Law” of Moses, very likely the original copy, which had been stored away in the house of God. At this point, it had survived for some 871 years. Jeremiah was so moved by the particular discovery that he wrote about the occasion at 2 Kings 22:8-10. About 180 years later, in 460 BCE, Ezra wrote about the same incident as well. (2 Chron. 34:14-18) Ezra was very interested in this, not only because of the importance of the event itself but he “was a skilled scribe in the Law of Moses, which Jehovah, the God of Israel, had given.” (Ezra 7:6, UASV) Considering Ezra’s position, the fact he was a historian, a scribe, he would have had access to all of the scrolls of the Old Testament that had been copied and handed down up to his time. In some cases, some were likely the inspired originals from the authors themselves. It would seem that Ezra was well qualified to be the custodian of the manuscripts in his day. – Nehemiah 8:1-2

In the days of Ezra and beyond, there would have been an increasing need for copying the Old Testament manuscripts. As you may recall from your personal Bible study, the Babylonians took the Jews into captivity for seventy years. Most of the Jews did not return upon their release in 537 BCE, and after that. Tens of thousands stayed in Babylon while others migrated throughout the ancient world, settling in the commercial centers. However, the Jews would pilgrimage back to Jerusalem several times each year, for religious festivals. Once there, they would be reading from the Hebrew Old Testament and sharing in the worship of God. Over a century later in Ezra’s day, the need to travel back to Jerusalem was no longer a concern, as they carried on their studies in places of worship known as synagogues, where they read aloud from the Hebrew Scriptures and discussed their meaning. As one might imagine, the scattered Jewish populations throughout the ancient world would have been in need of their own personal copies of the Hebrew Scriptures.

|

|

|

Within the synagogues, there was a storage room, known as the Genizah.[4] Over time, manuscripts would wear out to the point of tearing. Thus, it would have been placed in the Genizah and replaced with new copies. Before long, after the old manuscripts were built up in the Genizah, they would eventually need to be buried in the earth. They performed this duty, as opposed to just burning them, so the holy name of God, Jehovah (or Yahweh), would not be desecrated. Throughout many centuries, many thousands of Hebrew manuscripts were disposed of in this way. Gratefully, the well-stocked Genizah of the synagogue in Old Cairo was saved from this handling of their manuscripts, perhaps because it was enclosed and overlooked until the middle of the 19th century. In 1890, as soon as the synagogue was being restored, the contents of the Genizah were checked, and its materials were gradually either sold or donated. From this source, manuscripts that were almost complete and thousands of fragments have found their way to Cambridge University Library and other libraries in Europe and America.

Throughout the world, scholars have counted and cataloged about 6,300 manuscripts of all or portions of the Hebrew Old Testament. Textual scholars of the Hebrew Scriptures, for the longest time, had to be content with Hebrew manuscripts that only went back to the tenth century CE. This, of course, meant that the Hebrew Old Testament was about 1,400 hundred years removed from the last book that had been penned. This, then, always left the question of the trustworthiness of those copies. However, all of that changed in 1947, in the area of the Dead Sea, there was discovered a scroll of the book of Isaiah. In following years more of these precious scrolls of the Hebrew Scriptures were found as caves in the Dead Sea area yielded an enormous amount of manuscripts that had been concealed for almost 1,900 years. Specialists in the area of paleography have now dated some of these as far back as the third and second centuries BCE. The Dead Sea Scrolls as they have become known vindicated the trust that had been placed in the Masoretic texts that we have possessed all along. A comparative study of the approximately 6,000 manuscripts of the Hebrew Scriptures gives a sound basis for establishing the Hebrew text and reveals faithfulness in the transmission of the text. We have sill in existence many versions of the Old Testament, for instance, the Greek Septuagint, Aramaic Targums, the Syriac Peshitta, and the Latin Vulgate) were made directly from the Hebrew Old Testament.

Setting aside the critics of the Bible, what Jesus had to say about the Hebrew Scriptures, confirms for the Christians the integrity of the Old Testament. Jesus said, “And as for the dead being raised, have you not read in the book of Moses, in the passage about the bush, how God spoke to him, saying, ‘I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’”? (Mark 12:26) Jesus also said, “Has not Moses given you the law? Yet none of you keeps the law. Why are you seeking to kill me?” (John 7:19) Moreover, Jesus’ reference to the entirety of the Hebrew Old Testament confirms its integrity, “And he said to them, ‘These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things which are written about me in the law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.’”—Luke 24:44.

Isaiah 40:8 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

8 The grass withers, the flower fades,

but the word of our God will stand forever.

We certainly can have much confidence that while God did not preserve the Hebrew Scriptures by way of miraculous preservation, he did do so through restoration and by using innumerable, unnamed scribes, who gave their lives throughout 3,000 years, as well as using innumerable, unnamed textual scholars and translators, who have given their lives throughout the last 400 years.

Please Help Us Keep These Thousands of Blog Posts Growing and Free for All

$5.00

SCROLL THROUGH DIFFERENT CATEGORIES BELOW

BIBLE TRANSLATION AND TEXTUAL CRITICISM

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIBLICAL STUDIES / INTERPRETATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EARLY CHRISTIANITY

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHRISTIAN APOLOGETIC EVANGELISM

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TECHNOLOGY

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY

TEENS-YOUTH-ADOLESCENCE-JUVENILE

CHRISTIAN LIVING

CHURCH ISSUES, GROWTH, AND HISTORY

|

|

|

CHRISTIAN FICTION

|

|

|

|

|

|

[1] BCE means “before the Common Era,” which is more accurate than B.C. (“before Christ”). CE denotes “Common Era,” often called A.D., for anno Domini, meaning “in the year of our Lord.”

[2] Oxford Biblical Studies Online. (Retrieved Sunday, April 21, 2019)

http://www.oxfordbiblicalstudies.com/article/opr/t256/e634

Joshua, who took over for Moses and entered Canaan about 1460 BCE, mentions a Canaanite city called Kiriath-sepher, which means “City of the Book” or “City of the Scribe.”—Joshua 15:15, 16.

[3] Edward D. Andrews and Don Wilkins, THE TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT: The Science and Art of Textual Criticism (Cambridge, OH: Christian Publishing House, 2017), 546.

[4] BIBLE AND SPADE 2 (SPRING-SUMMER-AUTUMN 1982) Copyright © 1982

[5] There are many references to Moses’ recording legal matters throughout the Pentateuch: Exodus 24:4, 7; 34:27, 28; and Deuteronomy 31:24-26. Moses also recorded a song at Deuteronomy 31:22, and he is shown to have recorded of the itinerary of the long arduous journey through the wilderness, which is referred to at Numbers 33:2.

[6] James Swanson, Dictionary of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains : Hebrew (Old Testament) (Oak Harbor: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1997).

[7] Cornelius was a centurion, an army officer in charge of a unit of foot soldiers, i.e., in command of 100 soldiers of the Italian band.

[8] I.e. on your forehead

[9] I.e., promised

[10] I.e. Moses