TRUE OR FALSE …

IS IT TRUE OR FALSE THAT the Bible has been handed down through the ages without alteration?

IS IT TRUE OR FALSE THAT the hundreds of thousands of variations in Bible manuscripts weaken its claim that it is the Word of God?

Before we delve into answering the questions, let us look at an infinitesimal amount of information out of the tremendous mountainlike storehouse that we have today.

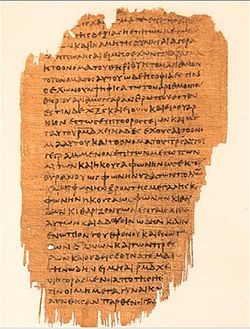

Even though the pages of old and torn fragmented papyrus are wasting away with age, the Chester Beatty Papyri are some of the most precious manuscripts on earth. As the account goes, they were in jars when they were dug out of a Coptic (Egyptian) graveyard about 1930 near the ruins of the ancient city of Aphroditopolis. Only the account of the Codex Sinaiticus could compete with this discovery. These papyrus pages were in codex form, handwritten, of course, being that they were copied between the mid-second century and the close of the third century C.E. Think about it, P45 was copied about 100-150 years after the death of the apostle John, who died about 100 C.E.

P45 (P. Chester Beatty I)

Contents: It contains sections within Matthew 20-21 and 25-26; Mark 4-9 and 11-12; Luke 6-7 and 9-14; John 4-5 and 10-11; and Acts 4-17.

Date: 200 – 225 C.E.

Discovered: Its origin is possibly the Fayum or ancient Aphroditopolis (modern Atfih) in Egypt (see Comfort, 157-9).

Housing Location: It is currently housed at the Chester Beatty Library, except for one leaf containing Matt. 25:41-26:39, which is at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna (Pap. Vindob. G. 31974). It was purchased by Chester Beatty of Dublin, Ireland, in 1931.

Physical Features: It has portions of thirty pages, but it is estimated that the original codex had 224 pages. Comfort tells us, “The first and last pages are blank and unnumbered, but pagination numbers are extant for 193 and 199. Approximately 20 cm broad x 25 cm high (5–6 cm thick, without binding); an average of 36–37 lines per page.” (Comfort and Barrett, 155)

Textual Character: P45 is an eclectic text-type and a Category I. In the Gospel of Mark, it reflects the Caesarean family, while the other Gospels reflect a mixture of Western and Alexandrian. In the book of Acts, it largely reflects the Alexandrian family, with some minor variants from the Western family.

Contents: P46 contains most of the Pauline epistles, though with some folios missing. It contains (in order) “the last eight chapters of Romans; all of Hebrews; virtually all of 1–2 Corinthians; all of Ephesians, Galatians, Philippians, Colossians; and two chapters of 1 Thessalonians. All of the leaves have lost some lines at the bottom through deterioration.”[15]

Date: 150 C.E.[16]

Discovered: Comfort says, “the Fayum, Egypt, or perhaps in the ruins of a church or monastery near Atfih (ancient Aphroditopolis).” (p. 203)

Housing Location: Ann Arbor, Mich.: the University of Michigan, Special Collections Library (P. Mich. inv. 6238).

Physical Features: In the original form, it would have had 52 folios,[17] which equals 104 leaves, 208 pages. However, in its current condition, 9 folios are missing. It is 15 cm x 27 cm, with 25–31 lines per page, a single column of 26 – 32 lines of text per page. Its pagination is 1 – 199.[18] P46 was written by a professional scribe.

Textual Character: P46 is an Alexandrian text-type / Category I. It is similar to Minuscule 1739.

P47

Contents: Rev. 9:10–11:3; 11:5–16:15; 16:17–17:2.

Date: 250 – 300 C.E.

Discovered: P47 (along with P45 and P46) it was discovered in the Fayum of Egypt or perhaps in the ruins of a church or monastery near Atfih, ancient Aphroditopolis.[19]

Housing Location: Dublin, Ireland: Chester Beatty Library.[20]

Physical Features: P47 has thirty leaves (60 pages); 14 cm x 24 cm; 26–28 lines per page. It was written in a documentary hand.[21] Comfort states, “The consistent abbreviation of numerals shows that the scribe was practiced at making documents. A second corrector (c2) made some additional corrections and darkened many letters.”[22

Textual Character: P47 is an Alexandrian text-type Category I. It most closely resembles Sinaiticus but is similar to two other manuscripts of Revelation: P18(250-300) and P24 (c. 300). Kenyon was first to examine the manuscript, saying, “It is on the whole closest to א and C, with P next, and A rather further away.”[23]However, after further investigation of P47, it has been shown that it “is allied to א, but not to A or to C, which are of a different text type.”[24] Comfort says, “We know that A, C, and P115 … form one early group for Revelation, while P47 and א form another.”[25]

Then, we have the Bodmer Papyri, which are a group of twenty-two papyri that were discovered in Egypt in 1952. They received their name from after Martin Bodmer who purchased them. The papyri contain portions from both the Old and New Testaments, as well as early Christian literature, not to mention Homer and Menander. The second oldest is P66, which dates to c. 200 C.E. In 2007 the Vatican Library acquired the oldest, the Bodmer Papyrus 14-15, that is, P75, dating to about 175-225 C.E. The most valuable New Testament manuscript of all 5,800+ is P75, which is a partial codex containing most of Luke and John.

P66

Contents: John 1:1–6:11; 6:35–14:26, 29–30; 15:2–26; 16:2–4, 6–7; 16:10–20:20, 22–23; 20:25–21:9, 12, 17. Does not include the pericope of the adulteress (7:53–8:11), earliest witness not to include this spurious passage.

Date: 150 C.E.

Discovered: Jabal Abu Mana.

Housing Location: Bodmer Library, Geneva.

Physical Features: 39 folios, equaling 78 leaves, 156 pages; 14.2 × 16.2 cm; 15-25 lines per page; pagination numbers from 1 to 156. The handwriting suggests that it was the work of a professional scribe.

Textual Character: P66 is a free text, with both Alexandrian and Western elements. In recent studies, Berner[29] and Comfort[30] maintain that P66 has preserved the work of three individuals: the original scribe (professional), a thoroughgoing corrector (diorthōtēs), and a minor corrector. However, in studies that are more recent James Royse argues that, aside from the possible exception of John 13:19, the corrections are all by the hand of the original professional scribe.[31]

The manuscript also contains, consistently, the use of Nomina Sacra. For example, in at least ten places one finds “[t]he common symbol …, the staurogram, which is made up of the superimposed letters tau (T) and rho (P) as an abbreviation for stauros / stauroō.”[32] The Staurogram was initially used as an abbreviation for the Greek words (σταύρος) stauros and (σταυρόω) stauroō in very early NT MSS, such as P45, P66, and P75, somewhat like a nomen sacrum.[33]

P72

Contents: 1 Peter 1:1–5:14; 2 Peter 1:1–3:18; Jude 1–25.

Date: c. 300 C.E.

Discovered: uncertain.

Housing Location: Cologny / Geneva, Switzerland; Vatican City, Bibl. Bodmeriana; Bibl. Vaticana.

Physical Features: P72 is “three parts of a 72-page codex; 14.5 cm x 16 cm; 16–20 lines per page. 1 and 2 Peter are paginated 1–36; Jude is paginated 62–68.”[34] It is in the documentary hand, meaning a person who was trained in preparing documents copied it. The manuscript contains “several marginal topical descriptors, each beginning with περι.” (Ibid.) The nomina sacra are used. This document also contains the Nativity of Mary, the apocryphal correspondence of Paul to the Corinthians, the eleventh Ode of Solomon, Melito’s Homily on the Passover, a fragment of a hymn, the Apology of Phileas, and Psalms 33 and 34.

Textual Character: P72 is of the Alexandrian text-type and the Alands have it as Category I. It is a free text, with certain uniqueness, often lacking careful attention in the transcription of a moderately reliable exemplar. P72 resembles P50.

P75

Contents: Luke 3:18–22; 3:33–4:2; 4:34–5:10; 5:37–6:4; 6:10–7:32, 35–39, 41–43; 7:46–9:2; 9:4–17:15; 17:19–18:18; 22:4–24:53; John 1:1–11:45, 48–57; 12:3–13:1, 8–10; 14:8–29; 15:7–8. It does not contain the adulterous story found at John 7:53–8:11.[35]

Date: 175 – 225 C.E.

Discovered: Pabau, Egypt.

Housing Location: Cologne-Geneva, Switzerland: Bibliotheca Bodmeriana.

Physical Features:

Textual Character: P75 is Alexandrian text-type and the Alands have it as Category I, strict text. The text is closer to Codex Vaticanus than to Codex Sinaiticus. It agrees with P111 (200-250).

It bears repeating what we discussed above. P75 (c.175–225) contains most of Luke and John and has vindicated Westcott and Hort for their choice of Vaticanus as the premium manuscript for establishing the original text. After careful study of P75 against Vaticanus, scholars found that they are just short of being identical. In his introduction to the Greek text, Hort argued that Vaticanus is a “very pure line of very ancient text.”[36] Of course, Westcott and Hort were not aware of P75, which would be published in 1961, about 80 years later.

The discovery of P75 proved to be the catalyst for correcting the misconception that early copyists were predominately unskilled. As we established earlier, either literate or semi-professional copyists produced the vast majority of the early papyri, and some were copied by professionals. The few poorly copied manuscripts simply became known first, giving an impression that was difficult for some to discard when the enormous amount of evidence surfaced that showed just the opposite. Of course, the discovery of P75 has also had a profound effect on New Testament textual criticism because of its striking agreement with Codex Vaticanus.

|

|

|

Copying Manuscripts Like These

The scribes of antiquity had a very tiring and tedious work, working hours every day hunched over a manuscript, using subpar materials that took much skill. The copyists were not inspired, moved along by the Holy Spirit, as was true of the original authors. In these work conditions, it would have been quite easy to misread a letter or miss a line of text, for even the professional scribe, committing an unintentional error.[18] Then, there were a few cases of intentional errors where scribes were seeking to harmonize the Gospels with each other, or making an effort in penning what he thought the original author meant than in copying the exact words. How many hundreds of thousands of copies were made over the centuries is difficult to even guess but at present, we have 5,800+ New Testament Greek manuscripts alone. Therefore, once an intentional or unintentional error was entered into a manuscript, it was perpetuated.

The Reliability of the Early Text

Even though many textual scholars credited the Aland’s The Text of the New Testament with their description of the text as “free,” that was not the entire position of the Alands. They did describe different texts’ styles, such as “at least normal,” “normal,” “free,” and “strict,” seemingly to gauge or weigh the textual faithfulness of each manuscript. However, like Kenyon, they saw a need based on the evidence, which suggested a rethinking of how the evidence should be described,

We have inherited from the past generation the view that the early text was a ‘free’ text, and the discovery of the Chester Beatty papyri seemed to confirm this view. When P45 and P46 were joined by P66 sharing the same characteristics, this position seemed to be definitely established. P75appeared in contrast to be a loner with its “strict” text anticipating Codex Vaticanus. Meanwhile the other witnesses of the early period had been ignored. It is their collations which have changed the picture so completely.[57]

While we have said this once, it bears repeating, as some of the earliest manuscripts that we now have evidence that a professional scribe copied them. Many of the other papyri confirm that a semiprofessional hand copied them, while most of these early papyri give evidence of being produced by a copyist who was literate and experienced. Therefore, either literate or semiprofessional copyist did the vast majority of the early extant papyri, with some being done by professionals. As it happened, the few poorly copied manuscripts became known first, establishing a precedent that was difficult for some to shake when the enormous amount of evidence emerged that showed just the opposite.

|

|

|

After a detailed comparison of the papyri, Kurt and Barbara Aland concluded that these manuscripts from the second to the fourth centuries are of three kinds (at least normal, normal, free, and strict). “It is their collations which have changed the picture so completely.” (p. 93)

- Normal Texts: The normal text is a relatively faithful tradition (e.g., P52, which departs from its exemplar only occasionally, as do New Testament manuscripts of every century. It is further represented in P4, P5, P12(?), P16, P18, P20, P28, P47, P72 (1, 2 Peter) and P87.[58]

- Free Texts: This is a text dealing with the original text in a relatively free manner with no suggestion of a program of standardization (e.g., p45, p46 and p66), exhibiting the most diverse variants. It is further represented in P9 (?), P13(?), P29, P37, P40, P69, P72 (Jude) and P78.[59]

- Strict Texts: These manuscripts transmit the text of the exemplar with meticulous care (e.g., P75) and depart from it only rarely. It is further represented in P1, P23, P27, P35, P36, P64+67, P65(?), and P70.[60]

Bruce M. Metzger (1914 – 2007) was an editor with Kurt and Barbara Aland of the United Bible Societies’ standard Greek New Testament and the Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament. In his A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Second Edition (1971, 1994), and other works, we have his view of the Alexandrian text-type as follows.

The Alexandrian text, which Westcott and Hort called the Neutral text (a question-begging title), is usually considered to be the best text and the most faithful in preserving the original. Characteristics of the Alexandrian text are brevity and austerity. That is, it is generally shorter than the text of other forms, and it does not exhibit the degree of grammatical and stylistic polishing that is characteristic of the Byzantine type of text. Until recently, the two chief witnesses to the Alexandrian text were codex Vaticanus (B) and codex Sinaiticus (א), parchment manuscripts dating from about the middle of the fourth century. With the acquisition, however, of the Bodmer Papyri, particularly P66 and P75, both copied about the end of the second or the beginning of the third century, evidence is now available that the Alexandrian type of text goes back to an archetype that must be dated early in the second century. The Sahidic and Bohairic versions frequently contain typically Alexandrian readings.

It is best if textual scholars focus their attention on the categories the Alands set out, as opposed to their over-generalization that the early period of copying was “uncontrolled” and “free.” The Alands’ rating system consisted of “at least normal,” “normal,” “strict,” and “free,” designed to evaluate the textual faithfulness of each manuscript. It seems that these terms were meant to gauge the level of control that the scribe showed in copying his exemplar. Manuscripts labeled “at least normal” referred to a copyist who at least gave some consideration to his task, namely, producing an accurate copy of the exemplar. “Normal,” on the other hand, referred to a copyist who permitted what was deemed a normal amount of variants within a copying of the exemplar. Therefore, “strict” referred to a scribe who allowed very few variants in his copy of the exemplar. Lastly, “free” would refer to a copyist who showed almost no regard for being faithful to the exemplar that he was copying.

|

|

|

It behooves the textual scholar to give much attention to the study of scribal habits, which really began with Ernest Colwell in 1969, who analyzed the scribal habits in P45, P66, and P75 by examining their singular readings.[61] Singular readings are variant readings that are found only in the manuscript being examined, not in any other extant documents. By studying these singular readings of a particular manuscript, we see into the habits of that scribe, namely, his pattern of textual variations, his interactions with the text. Colwell’s investigation was followed by a much more extensive study of singular readings by James Royse of the same manuscripts some twelve years later.[62] Then, we had Philip Comfort in his doctoral dissertation in 1997.[63] Comfort explains that his objective was “to determine what it was in the text that prompted the scribes of P45, P66, and P75 to make individual readings.” Comfort suggests that we forgo the categories of the Alands and “that textual critics could use the categories “reliable,” “fairly reliable,” and “unreliable” to describe the textual fidelity of any given manuscript.” This author would agree. Moreover, he shows “that many of the early papyri are ‘reliable,’ several ‘fairly reliable,’ and a few ‘unreliable.’” Comfort then logically explains, “One of the ways of establishing reliability (or lack thereof) is to test a manuscript against one that is generally proven for its textual fidelity. For example, since many scholars have acclaimed the textual fidelity of P75 (both for intrinsic and extrinsic reasons), it is fair to compare other manuscripts against it in order to determine their textual reliability.” (P. Comfort 2005, 268)

|

|

|

How do we know that the critical text NA28 and the UBS5 are reliable? In 1989, Eldon J. Epp noted that the papyri have added virtually no new substantial variants to the variants already known from our later manuscripts.[64] Even with the discovery of many other papyri over the last 25 years, the situation has remained the same. It can be said that after 135 years of early manuscript discoveries since Westcott and Hort of 1881, the above critical editions of the Greek New Testament have gone virtually unchanged. (Hill and Kruger 2012, 5) Hill and Kruger go on to say, “It also means that the fourth-century ‘best texts,’ the ‘Alexandrian’ codices Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, have roots extending throughout the entire third century and even into the second.” (p. 6)

The most reliable of the earliest texts are P1, P4, 64, 67, P23, P27, P30, P32, P35, P39, P49, 65, P70, P75, P86, P87, P90, P91, P100, P101, P106, P108, P111, P114, and P115. The copyists of these manuscripts allowed very few variants in their copies of the exemplars.[65] They had the ability to make accurate judgments as they went about their copying, resulting in superior texts. Whether their skills in copying were a result of their belief that they were copying a sacred text, or from their training, cannot be known. It could have been a combination of both. These papyri are of great importance when considering textual problems and are considered by many textual scholars to be a good representation of the original wording of the text that was first published by the biblical author. Still, “many of these manuscripts contain singular readings and some ‘Alexandrian’ polishing, which needs to be sifted out.” (P. Comfort 2005, 269) Nevertheless, again, they are the best texts and the most faithful in preserving the original. While it is true that some of the papyri are mere fragments, some contain substantial portions of text. We should note too that text types really did not exist per se in the second century, and it is a mere convention to refer to the papyri as Alexandrian, since the best Alexandrian manuscript, Vaticanus, did exist in the second century by way of P75.[66] It is not that the Alexandrian text existed, but rather P75/Vaticanus evidence that some very strict copying with great care was taking place.[67] Manuscripts that were not of this caliber of strict and careful copying were the result of scribal errors and scribes taking liberties with the text. Therefore, even though P5 may be categorized as a Western text-type, it is more a matter of negligence in the copying process.

The Aland Classification of Papyri as of 2002[68]

As Hill and Kruger put it, “if one accepts the Alands’ analyses, in 2002, forty out of fifty-five (or just under 73 percent) of the earliest NT manuscripts had Normal to Strict texts, and fifteen (or just over 27 percent) had Free to Like D texts. The single largest category, consisting of eighteen out of fifty-five (or nearly a third) of the earliest manuscripts, is the category of Strict text.” (Hill and Kruger 2012, 11) Therefore, it would be difficult to follow in the footsteps of previous authors who cite the Alands as their source in describing the early period of copying the Greek New Testament as “free,” or “wild,” “in a state of flux,” “chaotic,” “a turbid textual morass,” and so on.

|

|

|

The Primary Task of a Textual Scholar

The long-held task of the textual scholar has been to recover the original reading. Samuel Prideaux Tregelles (1813-1875) stated that the objective “of all textual criticism is to present an ancient work, as far as possible, in the very words and form in which it proceeded from the writer’s own hand. Thus, when applied to the Greek New Testament, the result proposed is to give a text of those writings, as near as can be done on existing evidence, such as they were when originally written in the first century.”[69] B. F. Westcott (1825-1901) and F. J. A. Hort (1828-1892) said it was their goal “to present exactly the original words of the New Testament, so far as they can now be determined from surviving documents.”[70]Throughout the twentieth century, leading textual scholars such as Bruce M. Metzger (1914-2007) and Kurt Aland (1915-1994) had the same goals for textual criticism. By it, Griesbach (1745-1812), Tregelles, Tischendorf (1815-1874), Westcott and Hort, Metzger, Aland, and other prominent textual scholars since the days of Erasmus (1466-1536), all gave their lives to the restoration of the Greek New Testament.

However, sadly, “more dominant in text critics’ thinking now is the need to plot the changes in the history of the text.”[71] While Bart Ehrman, David Parker, and J. K. Elliot are correct that we could never restore or establish the original words of the authors of the twenty-seven Greek New Testament books beyond question, it should still remain the goal, as opposed to the pessimistic attitude of late. If we sidestep the traditional goal of textual criticism, we are really abandoning textual criticism itself. While the textual scholar wants to track down the variants to the text through the centuries, this can only be done by realizing there was a beginning, i.e., the twenty-seven original texts. How does one identify an alteration in the text without knowing from what it was altered? While the NA28/UBS5 critical edition cannot be considered a 100% reproduction of the original twenty-seven books, textual scholarship should always work in that direction, or otherwise, what is the purpose? The authors of this publication are in harmony with the words of Paul D. Wegner, who writes, “Textual criticism is foundational to exegesis and interpretation of the text: we need to know what the wording of the text is before we can know what it means.” (Wegner 2006, 230)

|

|

|

Breaking Away From Bent Thinking

Psalm 119:101, 105, 165 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

101 I restrained my feet from every evil way,

so that I may keep your word.

105 Your word is a lamp to my feet

and a light to my path.

165 Abundant peace belongs to those loving your law,

and for them there is no stumbling block.

The Bible from the beginning has been greatly loved, respected, accepted, and followed by God’s true followers. Yes, copyist errors came into the manuscripts through the human imperfection of the scribes, yet not all copyist errors is ever found in one place ever, and most by far are easily solved by the reader, as they were simply small like typos. Again, no one given manuscript contains all of the errors. Yes, the Byzantine manuscript family is a corrupt text but not in the way most think. Corrupt means that it was made unreliable by errors or alterations. This is true but not in the all-encompassing way the Bible critic is Islam likes to claim.

Absolute Thinking: With this frame of mind, there is no middle ground. The Christian who hears the word(s) corrupt or corruption, scribal errors, unreliable, they see it as nothing more than a life-ending result. Corrupt does not mean absolutely 100% corrupt. Any changes in a text, no matter how small and how insignificant, it is still labeled as corrupted and unreliable because it is not as it once was. To have some copyist errors in each manuscript, with quite a number of them being spelling, a reversal of words, and the like, this is not the same as having all errors in a manuscript, not even remotely close. Even the worst corrupt Byzantine text and the Textus Receptus that made up the King James Version are not such that they impact what God’s Word teaches. We had the King James Version at the primary Bible of Christianity for over 400 years now and have the Bible doctrines changed because we have new, modern, better translations. No. Now, of course, the King James Version Onlyist would argue then why the need for new translations? Well, simply enough, just because a horse and buggy will get you to town, or an ox and plow will till the field, this does not mean we should not use the improved horse powered car and the horse-powered tractor.

Absolute Thinking: With this frame of mind, there is no middle ground. The Christian who hears the word(s) corrupt or corruption, scribal errors, unreliable, they see it as nothing more than a life-ending result. Corrupt does not mean absolutely 100% corrupt. Any changes in a text, no matter how small and how insignificant, it is still labeled as corrupted and unreliable because it is not as it once was. To have some copyist errors in each manuscript, with quite a number of them being spelling, a reversal of words, and the like, this is not the same as having all errors in a manuscript, not even remotely close. Even the worst corrupt Byzantine text and the Textus Receptus that made up the King James Version are not such that they impact what God’s Word teaches. We had the King James Version at the primary Bible of Christianity for over 400 years now and have the Bible doctrines changed because we have new, modern, better translations. No. Now, of course, the King James Version Onlyist would argue then why the need for new translations? Well, simply enough, just because a horse and buggy will get you to town, or an ox and plow will till the field, this does not mean we should not use the improved horse powered car and the horse-powered tractor.

Preservation Through Restoration

1 Peter 1:25 Updated American Standard Version (UASV)

25 But the word of the Lord endures forever.”[1]

And this is the word which was preached to you as good news.

[1] Lit for the age; quotation from Isa. 40:6, 8

IT IS TRUE OR FALSE THAT the Bible has been handed down through the ages without alteration.

ANSWER: This is false. The only group of people who believe such a preposterous thing are the King James Version Onlyist.

IT IS TRUE OR FALSE THAT the hundreds of thousands of variations in Bible manuscripts weaken its claim that it is the Word of God.

ANSWER: This too is false. Yes, the copying process of 3,600 years has led to copyist errors in our manuscripts but it has not impacted our being able to get at the truth of God’s Word.

God did preserve the Bible, but not the way most misinformed scholars, pastors, and churchgoers think. In the case of both the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament, it was preservation through restoration. Notice that the often-quoted Peter and Isaiah say, “the word of the Lord endures forever.” It does not say, ‘the word of the Lord endures forever without error.’ The Hebrew scriptures had the early sopherim (scribes) taking liberties with the text but not in extreme ways, and yes, some scribal errors slipped into the Hebrew text. Yet, this really never impacted anything. The most that could be said, for centuries, copyists and translators have had to determine a very minute amount of places what the original reading was. What we have today is a mirror-like reflection of the original in our English translations. The preservation came through restoration. Even the Greek New Testament, which had far more issues with scribal errors (variants), it never had such an impact as to block people from the truth of God’s Word.

God did preserve the Bible, but not the way most misinformed scholars, pastors, and churchgoers think. In the case of both the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament, it was preservation through restoration. Notice that the often-quoted Peter and Isaiah say, “the word of the Lord endures forever.” It does not say, ‘the word of the Lord endures forever without error.’ The Hebrew scriptures had the early sopherim (scribes) taking liberties with the text but not in extreme ways, and yes, some scribal errors slipped into the Hebrew text. Yet, this really never impacted anything. The most that could be said, for centuries, copyists and translators have had to determine a very minute amount of places what the original reading was. What we have today is a mirror-like reflection of the original in our English translations. The preservation came through restoration. Even the Greek New Testament, which had far more issues with scribal errors (variants), it never had such an impact as to block people from the truth of God’s Word.

You have some Obsessive Compulsive Grammarians who will rate a 1,000-page book of 760,000 words on Amazon as being full of errors when there may be 100 typos. This is the mentality of the Bible critics as well. Just as God allowed the perfect Adam and Eve to sin and had a perfectly good reason for allowing sin, old age and death to enter into humankind, he too had a very good reason for allowing imperfect human copyists to enter intentional and unintentional mistakes and errors into the manuscripts. We must remember that God also allowed imperfect humans to express their love for God’s Word through hundreds of textual scholars and translators giving their lives to the task of restoring the original and making a mirror-like reflection of that original in our translations.

Please Support the Bible Translation Work for the Updated American Standard Version (UASV) http://www.uasvbible.org

$5.00

SCROLL THROUGH THE DIFFERENT CATEGORIES BELOW

BIBLE TRANSLATION AND TEXTUAL CRITICISM

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIBLICAL STUDIES / INTERPRETATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EARLY CHRISTIANITY

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHRISTIAN APOLOGETIC EVANGELISM

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TECHNOLOGY AND THE CHRISTIAN

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY

TEENS-YOUTH-ADOLESCENCE-JUVENILE

CHRISTIAN LIVING

CHRISTIAN DEVOTIONALS

CHURCH HEALTH, GROWTH, AND HISTORY

|

|

|

CHRISTIAN FICTION

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.